A person’s health is under his teeth (Armenian proverb)

Lusine Khachatryan (Yerevan State University)

The purpose of this study is to explore Armeno-Turkish medical manuscripts, which are Turkish texts written in Armenian script, collected from the Matenadaran (Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan) from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries. including religious-philosophical treatises with sections on human physiology, drug books known as akhrapatin (ախրապատին), medical works and translations by both renowned and unknown authors, dictionaries in Turkish written with Armenian script, and practical manuals.

Most of these texts lack clear indications of their origin or time of compilation. Despite a recent surge of interest in Turkish manuscripts written in Armenian script (hereafter Armeno-Turkish), studies related to medical manuscripts have been largely overlooked by researchers. Limited information about these manuscripts is available only in the Matenadaran catalogues and in Hasmik Stepanyan’s bibliography.[1] Although Hakob Anasyan has explored the codicological features of Armenian medical manuscripts[2] his detailed analysis covers only four specific manuscripts from the Matenadaran.[3] Therefore, instead of exploring the codicological peculiarities of the manuscripts[4] this paper will focus on examining the main corpus of these codices, outlining the primary motivations of the authors and translators, and identifying the readership that had access to this translated and transcribed medical knowledge.

There are over thirty Armeno-Turkish medical manuscripts housed at the Matenadaran. These codices exhibit a wide variety of both content and linguistic styles. Notable[5] works include Ms 4026, which focuses on anthropology and includes a glossary of medicinal substances, and Ms 9559, a less decorated copy of Ms 4026 with consistent content but minor spelling differences. Ms 8102 is a translation and transcription of Dr. Zeyn al-Din al-Abidin’s work on nutritional therapy, highlighting the importance of diet in Ottoman medicine. Ms 10244, titled “Human Physiology,” is a translation of Abusaid’s work, intertwining Armenian and Turkish languages, and includes marginal annotations. Additionally, there are practical advisory manuals for everyday life, such as Ms 10346, which provides methods for obtaining oils and improving reproductive functions, and Ms 5538, an irregular mixed pharmacopoeia. These manuals, along with prescriptions for various diseases, offer useful household advice, such as methods for removing ink marks from clothes and recipes for making ink. The volume of unstudied material is substantial, making it challenging to provide exhaustive answers to all questions within a single article.

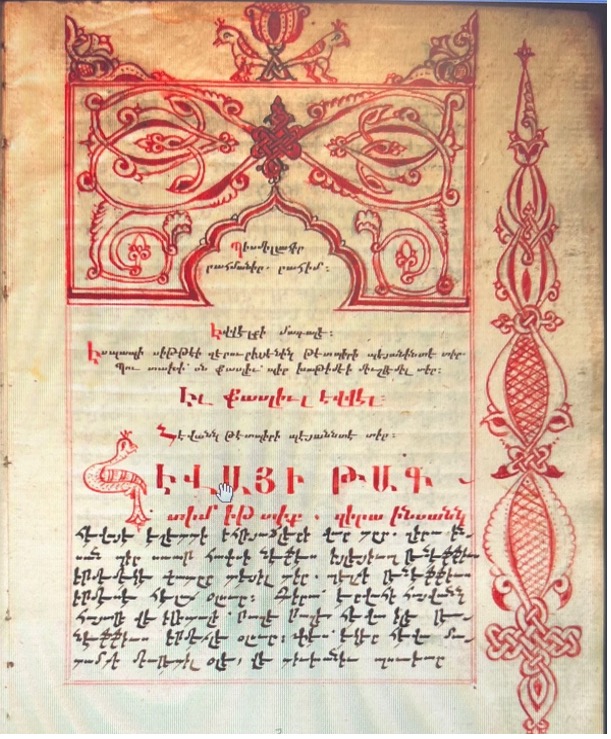

For instance, Ms 4026 lacks any reference to the author or translator, and the period and place of writing are unknown. The content focuses on anthropology and includes a glossary of medicinal substances derived from herbal, mineral, and animal origins. Judging by the degree of elaboration of the language, one assumes that it is transcribed from (Ottoman-) Turkish. The pages are decorated with ornaments, indicating a meticulous approach to its presentation (see illustration 1).

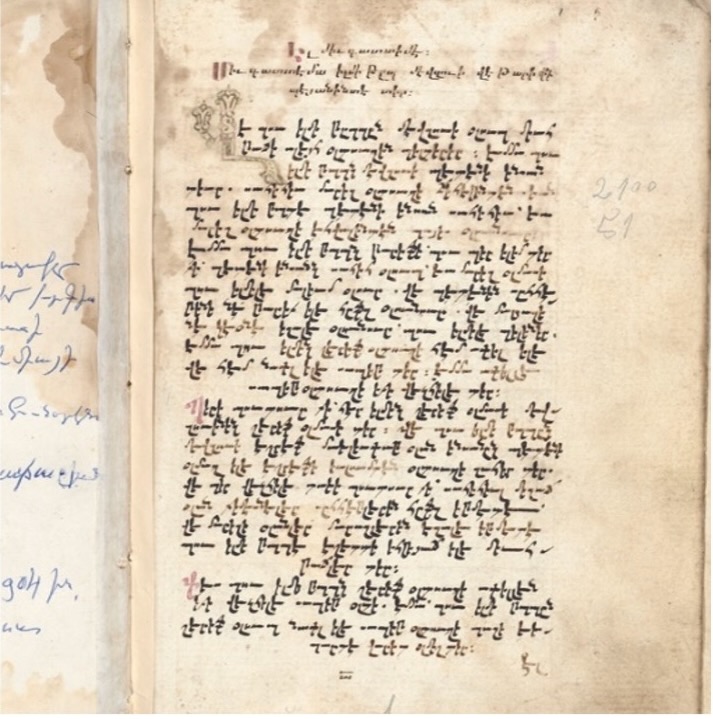

The pages of the copy of the same manuscript, Ms 9559, are less decorated (see illustration 2); the content remains consistent with the original, apart from a few spelling differences that may be attributed to transcription errors (see table below).

| MS 4026 | MS 9559 | Translation |

| Müḳaddema ilmi tıb mevzui ve tarifi beyaninde dür | Müḳaddema ilmi tıb mevzui ve tarifi beyaninde dir | introduction of medical science and description |

| Ve bu ilmi tıbıñ | Ve bu ilmi tıbın | and this knowledge of medicine |

| Ve bu ilmi tbbnñmevzui eşref maḫluḳat olan ınsanñ bedeni | Ve bu ilmi tbbnñmevzui eşref maḫluḳat olan ınsanñ bedeni | and this medicine the subject along with the noble creature human body |

Although no information about the author or the place of compilation of Ms 9559 has been preserved, the existence of a copy suggests its significance and popularity at the time. This indicates that the manuscript was likely widely circulated. Additionally, the text of this manuscript is very similar in both content and style to the texts of other notable manuscripts, such as Ms 8102, which covers nutritional therapy by Dr. Zeyn al-Din al-Abidin, and Ms 10244, which is titled “Human Physiology” and combines Armenian and Turkish languages with marginal annotations.

Ms. 8102 is a translation and transcription of the work by Dr. Zeyn al-Din al-Abidin, who held the position of chief physician in the hospital founded by Fatih in Istanbul during the reign of Sultan Murad IV (1623-1640). The manuscript, dating back to 1724, consists of two parts. The first part is a translation from Ottoman Turkish to Armenian, with a small head-note by the translator mentioning the source Turkish text (տաճիկ). The second part (ff. 24v-49v) contains an Armeno-Turkish transcription-translation of the work, which discusses nutritional therapy—considered one of the pillars of Ottoman medicine.[6] A great deal of attention was given to a proper diet, eating, and sleeping regime. More radical means of treatment were applied only when necessary, with surgical intervention being a last resort. Ms 8102 supports this view, with all chapters devoted to describing the nature of diets, food, and minerals, based on the paradigms of ancient Greco-Roman medicine, particularly Plato’s teaching on the four elements. The data from natural sciences and medical branches such as anthropology, pathology, pharmacology, and nutrition were also interpreted according to the principles of this theory about the cosmos (macrocosm) and man (microcosm). For example one reads Geyik eti ḫar yabis dir[7] (Venison is hot [and] dry); Taze balık rutub ve barid (Fresh fish is moist and cold); ḳuru yemişlerin tibatlerine dir (about the nature of dried fruits). [8] cevahirin tabietlerin ve ḫasselerin ve vicüdi insane mütealik fayide lerin beyan ider.[9] About the benefits of gems and patuskha (A type of very soft cotton cloth; sateen) for the human body. Like the other manuscripts here the author also refers to their predecessors, especially Galeonos (129c.-216c.), whose works, as emphasised by many researchers, formed the basis of the general concepts of Islamic and Ottoman medicine.[10] In this manuscript, the author often refers to Galeonos and Aristotle accordingly. Thus, one reads that “[…]Calinos hakım ider layık olan bu dur ki..[11] (Calinos considers it correct; what is proper is this.); or […] emma Calinos ider. Tazesi yurei sürer.[12] (But Calinos says, the fresh one is healthy) Or […] Arastatlis ider.[13](Aristotle says that).

Ms 10244 is the translation of the work by Abusaid, titled “Human Physiology.” Abusaid, an Assyrian scholar, resided among Armenians and Greeks in Cilicia, and was known for translating ancient Greek literature into Assyrian and later into Arabic, the lingua franca of the Muslim world at the time. His work significantly contributed to the preservation and dissemination of Greek knowledge throughout the Islamic world, facilitating cross-cultural intellectual exchanges and influencing various fields of study as philosophy, science, and medicine.[14]Among Abusaid’s works, only his treatise on human composition has survived in the Armenian version. It is noteworthy that the Matenadaran houses over thirty copies of this particular work,[15] although the Armeno-Turkish version remains unstudied. Additionally, Ms 10244 contains prescriptions and a pharmacy book, which are partly in Armenian. In these texts, Armenian and Turkish languages are intertwined in a mixed form. For instance, “ve (սօղուն) soghunler ki elan denilir” (soghunler: soghun [Armenian for reptile] + ler [Turkish suffix for plural], which translates to “soghunler that is called yilan” [Turkish for snake]. Another example is a chapter title written in Armenian: “Vasn steghtsman srti” (“For the creation of the heart”), followed by a mixture of Armenian and Turkish: “Yaratdi alah yuregi bir padişah cami vicude sıcak ve kuru edti onu ve cami herar eti kodu vicude sıcaklik yurekden gelir ve yurekde asla durmaz…” (And God created the heart as padishah for the whole body, made it warm and dry, and heat flows from the heart and never stops…)[16].

Apart from references, the manuscript contains marginal annotations and explanations to the main text, and it is not easy to determine whether the marginalia belong to the author or the readers. Medicine, like any other science, could not develop in isolation. When discussing Ottoman medicine, it must be viewed within the broader context of Islamic medicine, which was founded on various civilizational influences (e.g., Indian, Persian, Greek, etc.). Among these, the Greco-Roman paradigms were particularly influential. While authors of medical treatises acknowledged and respected many of the great masters who came before them, Galeonos is the most frequently referenced in their works. For example, in Ms 10244, the author-scribe mentions that “The masters of old carefully and deliberately chose medical knowledge among the sciences. These ancient masters valued and heeded the wisdom of both the Greeks and the Jews”.[17] “[…] ilacların faydalığı ki ḳulandiler ustaṫ hekim ler. ḳalianos. aristotel. ṗagrad. ve bunlerden yayıdi cemi miletlere. uṙumelie bağ(d)ade. aceme hinde ve cemi dunyaye ne şekil ki hagdan verildi yogardan ve olduler ṗirer ilimdar menşur hekim. ve bunların ustağınden çoḳ ler ustaṫ oldu ve tercube etṫiler ki biri bunlerden abu sayid denilir”… ( and the benefits of medicine which the master physicians such as Gallianus, Aristotle, and Bagrat, applied, and from them [their knowledge] spread to all nations like the Baghdad Greeks, Persians, the Indians, and to the whole world. In addition, it was gifted from God and they became educated and renowned doctors. And many of them from these masters became skilled gained experience and one of them was called Abusayid…)” [18]

Influence and Integration of European Medical Knowledge

Starting in the 11th century, European physicians sought out books written in Arabic. The works of Razes, Avicenna, Abul-Kasis, and El-Medjuchi were translated into Latin. However, the Arab scholars themselves were significantly influenced by and benefited from the works of Galeonos and the teachings of Hippocrates (450c.-380c. BC), Dioskorid (40c.-90c.)[19]. Although conventionally called Islamic medical paradigms had been circulating for a long time in the Ottoman environment, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the main directions of medicine gradually began to undergo changes.[20]

As Boyar emphasised, the earliest Ottoman Turkish translations of European medical texts appeared around 1500, marking the first transcultural contacts. [21] The turning period of the appropriation of European medical knowledge can be observed in the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century in the Ottoman Empire. [22] Manuscript Ms 9711, a bilingual Armenian and Armeno-Turkish treatise written in 1768, indicates that the Armenian readership was already somewhat acquainted with the works of European physicians. This work discusses various kinds of diseases, including mental diseases and human organ systems. For example, referring to the lymphatic system, the author uses the term “lymph” to describe it ([…] ona lınfa denir ve bu hem sulu dur hem zamgiyetli […] (it is called lymph, and it is both watery and thick…). [23]

The second part of the work analyses pathology in detail. Apart from the translation of Islamic medical works mentioned above, this work introduced European medical knowledge to its Armenian and Turkish speaking Armenian recipients. At the end of the text, the colophon provides details about the work as the following: “the work is translated into Ottoman Turkish by the great Spanish physician Julia from Latin language by the request of a doctor from Costandnopolis Karapet, then it was proofread by Manuel the priest, and the priest Georg appreciated doctor Karapet that he wrote this medical book both in Armenian and Turkish (տաճկեվար) for the benefit of my nation.”[24]

The several annotations on later owners (doctor Mkhitar from Kesaria, doctor Movses) as well as a verse quatrain in Armeno -Turkish dedicated to incurable diseases approve the wide circulation of the manuscript. It is clear from the manuscript’s text that this medical school already employs entirely different concepts and terminology compared to its predecessors, which are closer to our understanding of modern medicine. This evolution in medical knowledge warrants further investigation from the perspective of medical history.

Another example of reflection of the Ottoman – European medical transcultural contacts is the Ms 9583, entitled Ḫamsetu l-Hayati (Quintet of Hayati) and translated in 1772. According to the Armenian colophon of the translator and the scribe Nikolaios, it is Armeno-Turkish transcription (տաճկական տառից ի հայկական տառս փոխարկել) of the well-known work by Mustafa Ḫayatizade or Mustafa Feyiz. Additionally, Nikolaios mentioned that he provided “two-three” copy of the same work, which in its turn shows the demand and practical meaning of the work. Then he adds the following: “I could barely finish my book called Ḫamsetu l-Hayati, with great difficulty [and] I compiled Arabic and Persian dictionary according to alphabetical order especially for inexperienced [people]”[25]. Furthermore, he mentions that he dedicated his work to Doctor Jacob” and to the whole Armenian (Haikazian) nation.[26]

It is noteworthy that the glossary contains not only Arabic and Persian loanwords but also Latin equivalents and herbal names as the followings: Ali esphagos oti, yani diş oti Ali espagos / (It means toothwort, (plumbago europaea); Alleriḳ. Acḳarnıne dimek dür[27] (That is what they call hunger).

Moreover, the work obviously drew upon Latin texts authored by various European writers from the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth centuries and discusses diseases like syphilis and plague, which were newly discovered during this period and whose treatments were not readily found in the earlier treatises of renowned physicians.[28]

Folk Medicine and Practical Compendiums

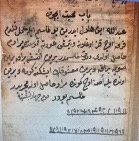

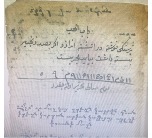

The manuscripts mentioned above represent examples of medical treatises that were known and circulated throughout the Ottoman Empire. Օne should not ignore the fact that a significant segment of the population lacked access to the healthcare facilities. To fully understand Ottoman medicine, it is crucial to study the branch of folk medicine, which combines practical herbalism, mysticism, and superstition. Rhoad Murphey highlighted the limited sources available for studying this topic, emphasising the importance of medical notebooks, diaries, and prescription books.[29] These seemingly inconsequential, small-scale edicts and charms played a crucial role for individuals lacking access to courtly literature. The prevalence of compendiums catering to folk medicine suggests their extensive utilisation. These compendiums, along with their prescriptions, incorporated elements of superstition and mysticism, as evidenced by the manuscripts under discussion. Among the manuscripts, there are those containing astrological charms as well as prescriptions. The Ms 9906, for example is a collection of prescriptions in several languages: Armenian, Armeno-Turkish, Persian and Arabic (illustration 3, 4).

|  |

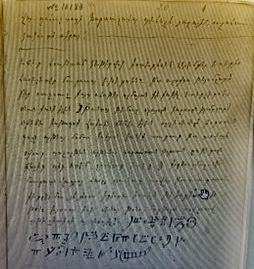

Ms 10183 contains medicinal names and translations of plant names in Armeno-Turkish, as well as magical words in a secret language and horoscopes. The stylistic composition of this manuscript differs from others, as it includes both prescriptions and incantations written in a secret language and Armenian script (illustration 3, 4, 5) Ms 5538 is an irregular mixed pharmacopoeia with a handwritten statement in Armenian. The second page (f. 001v) is titled “Chemistry,” but it discusses more about a prescription describing a method of obtaining a substance.

Ms 10346 is a similar bilingual manuscript, written in 1856 in Urfa (in the Armenian part of the manuscript named it as Edesia). According to the colophon, the work was compiled by the priest Petros as a gift to the son of surgeon Grigor (Cerrah Grigor): The works ranges from various prescriptions and methods for obtaining oils described in either Armenian or Armeno-Turkish, or a mixture of both languages. For example, there is an entry “yağ ğırınfili” (clove oil) and its recipe[30]. Sometimes lexical mixed Armenian and Armeno-Turkish clarifications are provided in the texts, such as in the following: […] as mormeni kokın, vor tach’ikn boghurtlan kasi/ (here is the root of blackberry (rubus), which Turks would say boğurtlan).[31]

Moreover, these brief collections of prescriptions provide more insight into practical domestic medicine than works that resemble religious-philosophical treatises in their meaning.

Thus, one can see that manuscripts written in Armeno-Turkish contributed to the proliferation and popularisation of Turkish as a scientific language of medicine for the time. The authors, through their supplementary dictionaries and marginal notes, sought to make the content as accessible as possible to both Armenian-speaking and Turkish-speaking members of the Armenian community, specifically noting in the records that “writing in two languages serves the benefit of the people.” These manuscripts were instrumental in disseminating knowledge throughout the multicultural and multiethnic Ottoman Empire, reaching beyond major educational hubs to even the peripheries. They played a crucial role in establishing Turkish as a scientific language of medicine. The inclusion of dictionaries, commentaries, and annotations by translators made this knowledge accessible to a broader audience. Despite their significant impact, these medical manuscripts have been largely overlooked by researchers and warrant in-depth, comprehensive study. Furthermore, discovering equivalent originals and performing comparative analyses would offer valuable insights into the evolution and cross-cultural exchanges in medical knowledge.

[1] Hasmik Stepanyan, “ Ts‘uts‘ak hayeren dzeṛagreri hayataṛ turk‘eren nyuteri ev hayataṛ turk‘eren dzeṛagreri” [Catalogue of Armeno-Turkish materials of Armenian manuscripts and Armeno-Turkish manuscripts] (Yerevan: Published by the author, 2008), 245-251.

[2] All the examined manuscripts are listed under the title “Medicines” in the Matenadaran catalogues.

[3] Hakob Anasyan, “ ZhĚ darum gruats hayatar turkeren ch‘ors bzhshkaranner”, [Four Armenian Script Turkish medical works compiled in the eighteenth century which were MSs 4026, 8102, 9711, 9583 ], Shoghakat‘ (1977): 100-10; See Haykakan matenagitut‘yun E-ZhĚ darerum, Bzhshkagitakan nyut‘er- Germanos Kostandnopolsets‘i” [The Armenian Bibliography in the Fifth- eighteenth century, Medical materials] Vol. 3. (Yerevan; Zangak-97, 2004), 40-45.

[4] All the examined manuscripts are listed under the title “Medicines” in the Matenadaran catalogues.

[5] The initial observations indicate that the mentioned works revolve around core concepts, conveying the author’s and/or the scribe’s own additions and ideas in a literary language characteristic of the era. These initial findings suggest that the manuscripts house important and professionally valuable works from that period, which are under the scope in the further study.

[6] Miri, Sheffer-Mossenson, Ottoman Medicine Healing and Medical Institutions, 1500-1700, (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2009), 30.

[7] Ms 8102, Mashtots Matenadaran, Ancient Manuscripts collection (hereafter Matenadaran), f. 030v. All translations are my own unless otherwise stated. The Armeno-Turkish transcriptions are according to the scheme suggested by Hülya Çelik and Ani Sargsyan. See “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies”, Diyâr, 3. Jg., 2 (2022): 161–189.

[8] Ms8102, Matenadaran, f.036r.

[9] Ms8102, Matenadaran, f.041v.

[10]Arslan Terzioğlu, “Galen and his Influence on Turkish-Islamic Medicine,” in Beiträge Zur Geschichte Der Türkish-Islamischen Medizin, Wissenschaft und Technik, ed. by Arslan Terzioğlu et al., 11-17. (Istanbul: Isis, 1996).

[11] Ms 8102, Matenadaran f. 027r.

[12] Ms 8102, Matenadaran, f. 037r.

[13] Ms 8102, Matenadaran, f. 041v.

[14] Nükhet Varlık states that there were very few books in spoken Turkish in the palace library, “The overwhelming majority of titles in this section is written in Arabic—the lingua franca of medicine in the Islamicate world in the mediaeval and early modern eras. There are eighteen titles in Persian, and five in Turkish.” Varlık, Nükhet. “Books on Medicine: Medical Knowledge at Work.” In Treasures of Knowledge: Studies and Sources in Islamic Art and Architecture, Supplements to Muqarnas, An Inventory of the Ottoman Palace Library (1502/3–1503/4), Volume I, 527-557. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

[15] Stella Vardanyan, Hayastani bzhshkut’yan patmut’yun, hnaguyn zhamanaknerits minch’ev mer orerĕ, [The history of Armenian medicine from ancient times to the present day], (Yerevan: Qnnaser, 2000.), 122.

[16] Ms 10244, Matenadaran, f. 004v

[17] […]Doğru ve kikir ile seçmiş ler ilimdalar hekimlik ustalığı esḳi zaman ustaleri ve rumların ve yahudilerini bilmişler ve doymişler[…], see Ms 10244 Matenadaran, f. 002r.

[18] Ms10244, Matenadaran, f 002r.

[19] Karapet Basmadjian, Amirdovlatʿ of Amasya, Angitats Anpet: am Bararan bzhshkakan niwtʿosʿ[Ignorant useless, dictionary of medical materials], Vienna, 1926, 4.

[20]Spyros N. Michaleas, Konstantinos Laios, Gregory Tsoucalas, and Georges Androutsos, “Theophrastus Bombastus Von Hohenheim (Paracelsus) (1493–1541): The Eminent Physician and Pioneer of Toxicology”, Toxicology Reports 8 (2021): 411-414.

[21] Ebru Boyar, “Medicine in Practice: European Influences on the Ottoman Medical Habitat.” Turkish Historical Review 9 (2018): 214-215.

[22] Ebru Boyar, “Medicine in Practice: European Influences on the Ottoman Medical Habitat,” 217.

[23] Ms9711, Matenadaran, f.018v.

[24] Ms 9711, Matenadaran, f. 171r.

[25] Ms 9583, Matenadaran, f.203r-250v.

[26] Ms 9583, Matenadaran, f. 200r.

[27] Ms 9583, Matenadaran, f. 203r.

[28] Sisman Cengiz, “Transcending Diaspora: Studies on Sabbateanism and Dönme. Hayatizade Mustafa Efendi (Moshe ben Fafael Abravanel), The Physician- in-Chief of the Ottoman Palace: Marrano Legacy, Ottoman Medicine and the Sabbatean Movement, Libra (2016): 83.

[29]Rhoad Murphey,”Ottoman Medicine and Transculturalism From the Sixteenth Through the Eighteenth Century.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 66, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 376-403.

[30] Ms 10346, Matenadaran, f. 002v.

[31] Ms 10346, Matenadaran, f. 007r.