Tobias Sick (University of Münster)

The reception of Persianate literature in the form of translations in the Ottoman Empire as a field of study has gained more traction in recent years; however, studies pertaining to such translations in the context of Armeno-Turkish have hitherto not featured prominently in the literature.[1] Yet, there are examples that attest to the transmission of translated Persian literature in Armeno-Turkish already during the eighteenth century, attesting to the reception of such works in Armenian-speaking strata of Ottoman society as well. One case in point is the manuscript held under the shelf-mark Ms. no. 19 in the library of the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna, which contains a Turkish translation of the Persian poetic advice treatise Pandnāma-yi ʿAṭṭār in the Armenian script, and constitutes the focus of the following passages.[2]

The so-called Pandnāma-yi ʿAṭṭār or ʿAṭṭār’s Book of Wise Counsel (from here on Pandnāma) forms an important part of the tradition of Persian advice literature as featured in the mas̱navī form. While most likely not penned by its eponym, the Persian Sufi figure Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār (d. 618/1221), this poetic advice treatise was employed as a didactic textbook in a vast space that is largely congruent with the notions of the Persianate world or Shahab Ahmed’s Balkans-to-Bengal complex.[3] Its reception and transmission was particularly pronounced in the Ottoman Empire, where it was employed mostly in educational contexts throughout the early modern period, namely for the study of Persian (poetics), moral instruction, as well as a more accessible source for the supposed mystical thought of ʿAṭṭār.[4] Within this continuous reception, the Pandnāma was translated into Turkish in numerous instances, with at least one dozen verse translations (terceme/tercüme) and a multitude of commentaries (şerḥ) attested for the work, featuring various ways of rendering the contents of the source text in Turkish (as well as Arabic) and different formats of visual display in the respective manuscript corpora.[5]

The most popular of the verse translations is the Terceme-i Pendnāme-i ʿAṭṭār penned by the sixteenth-century divan poet Emre,[6] which is a Turkish rendition of the Pandnāma that was produced in the year 964/1556 in a courtly environment, namely on request of Prince (şehzāde) Bāyezīd during the reign of his father, Sultan Süleymān I (r. 926–974/1520–1566).[7] In the preface to the translation (titled “Der sebeb-i terceme şöden-i īn nāme”, On the Reasons for Translating this Book), the translator narrates the request of the prince as follows:[8]

Table 1: Excerpt from the translator’s preface of Emre’s translation (verses 41-42).

| 41 | دیدی ترکی ایله بوکا جامهٔ | طوتمش الده اشبو زیبا نامهٔ |

| 42 | جلوه قلسون قوم رومه دمبدم | رومی خلعتده بو محبوب عجم |

He held in his hand this beautiful book, / said: ‘make for a Turkish garment’.

This beloved of Persia, in a Rūmī robe, / shall entice the people of Rūm perpetually.

Taking up this request, Emre produced a translation consisting of 65 chapters and 957 verses (distichs), which subsequently came to be the most popular of the many verse translations of this work (judging from the extant manuscript corpora).[9] This translation also includes, beyond the contents of the Persian source text, a Persian prelude, a translator’s preface, and a concluding chapter (all three of which were produced solely by the translator). In terms of the style of translation, the Turkish (Türkī) version of the Pandnāma exhibits several characteristics that are typical for Ottoman translations of Persian mas̱navī works at the time: While generally adhering to the structure and contents of the source text, the translation includes large portions of Arabic and, in particular, Persian words and phrases also included in the original,[10] and, with respect to the contents, occasionally exhibits instances of elaboration, disambiguation, and omission, as well as changes in the chapter structure (some of which might also stem from variants in the manuscripts used for translating).

As a fully substitutive translation work, in its manuscript corpus this translation presents only the Turkish rendering of the Pandnāma’s contents (in contrast to some of the other translations), and was likely created to be employed in a fashion similar to the Persian original, namely in educational contexts, especially for the instruction of adolescents, as Emre suggests at the end of the work himself:[11]

Table 2: Excerpt from the concluding chapter of Emre’s translation (verse 953).

| 953 | بونی ازبرلتدر اکا ای سعید | گر دلرسك اوله فرزندك فرید |

If you want your child to be one of a kind, make them memorise it, oh happy one.

In recent years, the translation of Emre has been edited in the Latin script several times and was discussed in several publications and unpublished doctoral dissertations; however, the existence of an Armeno-Turkish rendition of the Pandnāma and, in particular, the very translation of Emre has not been discussed previously.

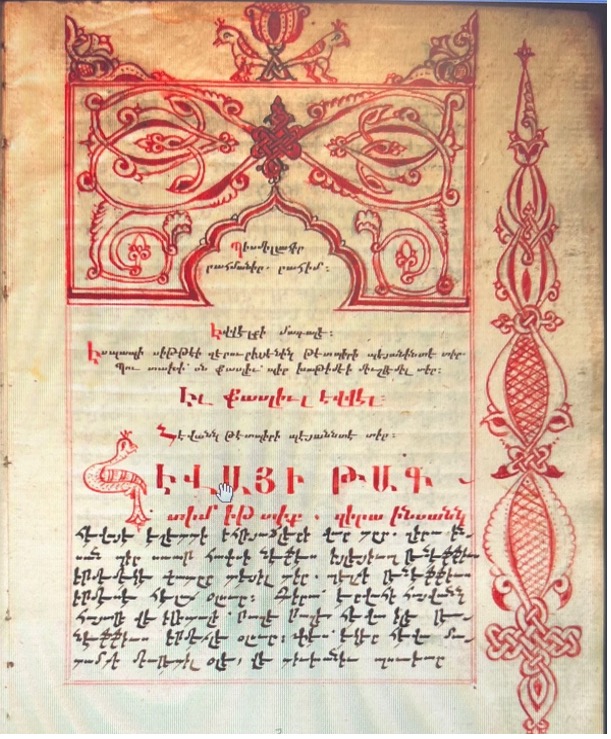

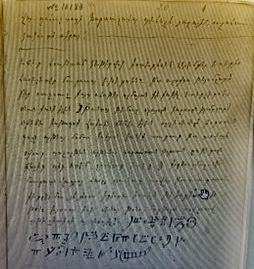

The manuscript in question, MS no. 19 held in the library of the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna, features 56 folios altogether with the text presenting a consistent 21 lines per page.[12] According to the title of the manuscript, the contained work is the Pearl-Adorned Pendname (Mücevher Pendname, Միւճէվհէր Փէնտնամէ) of ʿAṭṭār, which is located between fols. 3a and 54a.[13] The codex measures 215×155 millimetres (the text 160×100) and is bound in paper with a leather book spine. The text itself is held mostly in the Notrgir script,[14] rendered in both black and red ink (mainly for headings and the initials opening a distich), and exhibits large decorative and, at times, zoomorphic initials at the beginnings of the individual chapters. On the first page, the copy features a coloured headpiece with a floral pattern but no title, as the title phrase is given below (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Opening page of the work on f. 3a.

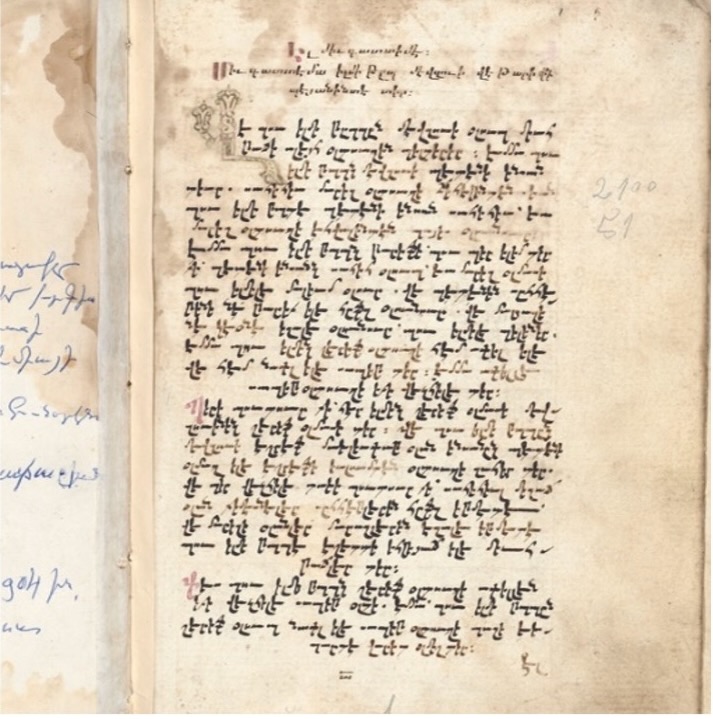

Comparing the beginning and final sections of the work, especially the preface, it becomes clear that the present text is not a novel, Armeno-Turkish translation of the Persian Pandnāma but an Armeno-Turkish rendering of the translation of Emre from 964/1556. Apart from the prelude and translator’s preface, even the final verses of Emre’s translation, which feature the date as well as the nome de plume of the translator, were transferred into this rendition (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2: The final verse featuring the date of Emre’s translation on f. 54a.

AT transcript: տիտիլէր թարիխիտէ էյ մէրտիքեար / տիտիմ իշտէ նիւհի սատ շ[ա]ստիւ չիհար

AT transliteration:Didiler tariḫide ey merdikyar / dedim işde nühi sad ş[a]sdü çehar.

Translation: They said, ‘tell [us] the date, oh man of deeds’, / thus, I said ‘nine hundred and sixty and four’ (964/1556–1557).

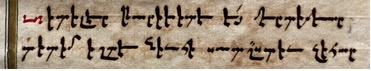

Fig. 3: The taḫalluṣ of Emre on f. 54a.

AT transcript: էյ գամու տիւշմիւշլէրէ սէն տէսթիրէս / պօյի աֆֆըն էմրէի կիւմրահէ պէս.

AT transliteration: Ey ḳamu düşmüşlere sen destires / Boyi affın Emrei gümrahe bes.

Translation: Oh, for many fallen ones you reach / the fragrance of your forgiveness suffices for erring Emre.

The manuscript also features a colophon succeeding the final verse of the translation on f. 54a, which consists of a concluding phrase and the date 1224/1775. Due to the absence of any other information, it is unclear when precisely this new rendition was produced and whether the manuscript at hand is a copy or perhaps its single textual witness. In any case, the colophon attests to the existence of an Armeno-Turkish version of Emre’s terceme more than two hundred years after the completion of the work.

In terms of its structure, this new rendition features almost all parts of Emre’s work, including also the translator’s preface and conclusive passage attesting to the completion of the translation in 964/1556, making clear the relation between the two texts.

Table 3: Contents of the manuscript.

| Fols. | Section |

| 3a–4a | Prelude |

| 4b–6a | Translator’s preface |

| 7a–54a | Chapters 1–53 |

| 54a | Conclusion |

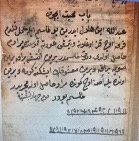

Indeed, even the Persian prelude created by Emre was rendered into the Armenian script, constituting effectively an Armeno-Persian passage of 21 verses. In doing so, the Armenian alphabet was employed in a fashion similar to the Turkish passages, including the rendering of the Persian iżāfa (“ի”) also used in Ottoman genitive constructions, an apostrophe-like symbol to signify the letter ʿayn in the Arabic alphabet (see fig. 4), and the presence of mouillé consonants (such as “քեամ / kyam” in the Persian word “kām-bakhsh”).[15] As becomes clear from the vowels featured in this passage, the Persian was apparently read and, therefore, written in a Turkified pronunciation.[16] Compare the first four hemistichs of both versions (fig. 5):[17]

Fig. 4: Rendering of the Arabic-script letter ʿayn in the passage cited below.

Fig. 5: Opening verses of Emre’s prelude in Armeno-Turkish (f. 3a).

Table: 4: Comparison of a passage from the Persian prelude of Emre’s translation.

| Transcript AT | Transliteration AT | Transliteration P | Transcript P |

| Իպթիտա քէրտէմ պէնամի ան քէրիմ | ibtida kerdem benami an kerim | ibtidā kardam bi-nām-i ān karīm | ابتدا کردم بنام آن کریم |

| միւպտիի’ քէվնէյն սուլդանի գատիմ | mübdiʿi kevneyn sulṭani ḳadim | mubdiʿ-i kawnayn sulṭān-i qadīm | مبدع کونین سلطان قدیم |

| փատիշահի միւհեիեի ա’զմի րէմիմ | padişah-i mühyiyi ʿazmi remim | pādishāh-i muḥyī-yi ʿaẓm-i ramīm | پادشاه محیی عظم رمیم |

| քեամիճան պախշիւ տիլիւ ճանի եէթիմ | kyamican baḫşü dilü cani yetim | kām-bakhsh u kām-kār-i har yatīm | کام بخش و کامکار هر یتیم |

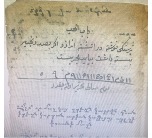

In this fashion, all verses of the Persian prelude are presented in this copy, in addition to the Turkish translator’s preface, which is also given in full. The following chapters of the translation proper are then introduced via longer titles (which are to my knowledge not present in the extant copies of Emre’s work in the Arabic script), offering a description of their contents as is the case, for instance, in the title of the first chapter (fig. 6):

Fig. 6: Title of the first chapter (f. 7a).

AT transcript: Պիրինճի Պապ/ Պու պահըր մուսաննըֆըն համտիւ շիւքր իթմէքլինկի պէեանինտէտիւր.

AT transliteration: Birinci bab / bu bahır musannıfının hamdü şükr itmeklingi beyanindedür.

Translation: First chapter: This part is on the author’s praise [of God].

All of the 53 chapters apparently were to carry titles such as the one above, even though some were not inserted in this copy. The main difference in the number of chapters when compared to copies of the Arabic-script version of Emre’s work is due to the combination of several chapters in the Armeno-Turkish version, such as chapter 46, which combines chapters 53 and 54 (in the edition of Bilgin).[18] Apart from such fusions of chapters, which are present in part of the manuscript corpus of the Arabic-script version as well, the present rendition adheres rather strictly to the contents of Emre’s translation, both with respect to the verse numbers within the individual chapters as well as the precise wording of the verses. Thus, the Armeno-Turkish rendition cannot be considered a proper case of tradaptation, as it faithfully renders the Turkish of the source into Armenian letters.[19] As an example of the contents of the work, consider the following example from chapter 10:

Fig. 7: Beginning of chapter 10 on f. 13b.

Table: 5: A passage from the Armeno-Turkish version of Emre’s translation.

| Transcript AT | Transliteration AT |

| Աֆիեէթ իսթէրսէն էյ եարի ա’զիզ | Afiyet istersen ey yari ʿaziz, |

| արա անի չար չիզ իչինտէ թիզ | ara çar çiz içinde tiz. |

| Պիրի էյմէնլիք պիրի նի’մէթ տիւրիւր | biri eymenlik biri niʿmet dürür |

| պիրի սըհհաթ պիրի ազատ տիւրիւր | biri sıhhat biri azad dürür |

If well-being is what you seek, oh dear, look for it in four things, quickly.

One is safety, one is happiness; one is bodily health, and another one, freedom.[20]

Yet, there are also some parts of Emre’s translation which were not transferred into the Armeno-Turkish version and constitute a modification or adaptation. While these changes do not pertain to any of the characteristic passages that make possible the identification of Emre’s translation, they concern another set of chapters, namely the second and third chapters of the translation, which contain altogether 17 verses with praise for the Prophet Muḥammad, the first four caliphs, and the some of the founding figures of the Sunni religious schools.[21] Thus, the transfer of the work into Armeno-Turkish entailed the preservation of the largest portion of the work’s admonishing contents, including those parts which ensured the visibility of the original translator, whereas the distinctly Islamic passages of the translation were omitted.

As for its production, the manuscript (and, thus, the Armeno-Turkish rendition itself) bears no marks attesting to the specific context of its creation. Concerning its circulation, the manuscript bears – apart from the stamp attesting to its presence in the current library – only a small note on f. 2a stating that it was gifted to the Mekhitarist Congregation in Trieste on 1 February 1808 by a certain Philippus Tatarian Arynthiants.[22] Thus, the copy’s creation and whereabouts before 1808 remain unclear; however, it still serves to evidence yet another layer of transmission of the Pandnāma in the Ottoman context and, perhaps, one that is not related to settings of Islamic education.

On the usage of the Pandnāma in its Armeno-Turkish variety, not many historical accounts can be found. Yet, it is likely that it was produced to be employed in educational contexts, as was the case with the Persian original and Emre’s translation in the Arabic script as well. In terms of authors making mention of the work in contexts pertaining to Armenian or Armeno-Turkish, the Pandnāma is referenced, for instance, in the Armeno-Turkish primer to the Ottoman Turkish language and orthography titled Miftāhü’l-ʿulūm (Key to the Sciences) by Hagop Paşayan (published in 1873). In the preface to the book, the author mentions the “Counsels of ʿAṭṭār” (Pend-i ʿAṭṭār) among other famous works of Persian advice literature, such as the Gulistān of Saʿdī (d. 691/1292) or Nakhshabī’s (d. 751/1350) Ṭūṭīnāma, as being employed typically for the teaching of the “Ottoman language”.[23] Given the application of the Persian original and the translation of Emre in such contexts and the awareness of later authors such as Paşayan on this didactic applicability, the Armeno-Turkish rendition of the work might have been conceptualised for such an application as well. Even though Paşayan’s book appeared roughly a century after the manuscript at hand was produced, this educational usage of the Pandnāma in the Ottoman Empire persisted between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries and, thus, appears to have reached another important stratum of Ottoman society in its Armeno-Turkish form. Indeed, perhaps the intrinsic structure of the Pandnāma, namely its direct approach in giving advice, its linguistic accessibility, and the absence of passages on distinctly Islamic historical figures outside of the second and third chapters made it seem especially suitable to be rendered into another alphabet to be used in a non-Islamic context of moral or linguistic instruction.

Constituting thus an important albeit single witness to the reception of the (translated) Pandnāma within Armenian-speaking strata of Ottoman society during the eighteenth century, the present manuscript further serves to show the invariances and changes that the transfer into the Armeno-Turkish included for such instances of translated Persian literature. Yet, many questions remain in absence of more detailed contextual information, and, likely, further instances of this and other versions can be found, as there are some indications for other copies of the Pandnāma in the Armenian script.[24] However, after this brief discussion, the blog entry must end, and it does so with the Armeno-Turkish colophon on f. 54a of the manuscript, reading:

Fig. 8: Colophon of the work on f. 54a.

Թէմէթթիւլքիթապ պի ա’վնիլլահիլ մէլիքիւլ վէհհապ.

Temettül kitab bi ʿavni’llahil melikül vehhab.

Completed is the book with the help of God, the ever-bestowing King.

References

Ambros, Edith Gülçin, Hülya Çelik, and Ani Sargsyan: “Intertwined Literatures: Karamanlı, Armeno-Turkish, and Regular Ottoman Versions of the Köroğlu Folktale”, in: Evangelia Balta (ed.): Literary and Cultural Crossroads in the Late Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: Boyut, 2024), pp. 1–54.

Bilgin, Azmi: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr (Istanbul: Enderun Kitabevi, 1998).

Çelik, Hülya and Ani Sargsyan: “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies”, in: Diyâr, 3/2 (2022), pp. 161-189.

Dashian, Jacobus: Catalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Mechitharisten-Bibliothek zu Wien (Wien: Mechitaristenbuchdruckerei, 1895).

Emre, Terceme-i Pendnāme-i ʿAṭṭār, MS Süleymaniye Yazma Eser Kütüphanesi, İzmir 612.

Der Matossian, Bedross: “The Development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T‘rk‘erēn) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire”, in: Intellectual History of the Islamicate World, 8/1 (2020), pp. 67-100.

Drkić, Munir and Ehsan Reisi: “Dalāyil va ās̱ār-i ravāj-i Pand-nāma-yi mansūb ba ʿAṭṭār dar Būsnā” (The Causes and Effects of the Spread of the Pandnameh of Attar in Bosnia), in: Gawhar-Gūyā,14/2 (2021), pp. 151-170.

Kirakosyan, Hasmik: “The Orthographic Rules of the Eighteenth Century Armeno-Persian Gospels of the Matenadaran”, in: Iranian Studies, 53 (2020), pp. 295-330.

Kirakosyan, Hasmik and Ani Sargsyan: “The Educational Role of the Late Medieval Persian-Ottoman Turkish Bilingual Dictionaries”, in: Turkic Languages, 22/2 (2018), pp. 167-174.

Paşayan, Hagop: Miftāhü’l-ʿulūm (Istanbul: Aramyan Matbaası, 1873).

Strauss, Johann: “What was (Really) Translated in the Ottoman Empire? Sleuthing Nineteenth-century Ottoman Translated Literature”, in: Marilyn Booth (ed.): Migrating Texts, Circulating Translations around the Ottoman Mediterranean (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), pp. 55-94.

Johann Strauss, “Who Read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th–20th Centuries)?”, in: Middle Eastern Literatures, 6/1 (2003), pp. 39–76.

Yazar, Sadık: Anadolu Sahası Klâsik Türk Edebiyatında Tercüme ve Şerh Geleneği, Ph.D. dissertation (Istanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi, 2011).

Zweng, Kandida: “Pandnama: Kritische Textausgabe und Übersetzung der Urduinterpretation des klassischen persischen Lehrgedichtes Pandnama”, in: Acta Orientalia, 61 (2000), pp. 23-144.

[1] I want to thank Ani Sargsyan for making me aware of this manuscript and for her help with some of the readings. Moreover, this contribution was made possible through the Andreas Tietze Memorial Fellowship in Turkish Studies of the Department of Near Eastern Studies of the University of Vienna, and I am deeply grateful for the support and research opportunities I received in Vienna during September and October 2024. Furthermore, the research was conducted within the framework of the Emmy Noether Junior Research Group TRANSLAPT (uni.ms/translapt). Then, I want to also express my gratitude towards the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna and especially the librarian, P. Simon Bayan, for granting me access to the manuscript at hand. For studies addressing the proliferation and reception of (translated) Armeno-Turkish literature (primarily during the nineteenth century), see Ambros/Çelik/Sargsyan: “Intertwined Literatures: Karamanlı, Armeno-Turkish, and Regular Ottoman Versions of the Köroğlu Folktale”; Strauss: “What was (Really) Translated in the Ottoman Empire?”; idem: “Who Read What in the Ottoman Empire?”; Der Matossian: “The Development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T‘rk‘erēn) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire”. While not translations in the literary sense, the role of Persian-Turkish dictionaries in educational contexts have been discussed by Kirakosyan/Sargsyan: “The Educational Role of the Late Medieval Persian-Ottoman Turkish Bilingual Dictionaries”.

[2] For the entry in the physical catalogue, see Dashian: Catalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Mechitharisten-Bibliothek, p. 18.

[3] On the notion of the Persianate world, see Green: “Introduction: The Frontiers of the Persianate World”; on the Balkans-to-Bengal complex, see Ahmed: What is Islam?, pp. 73-75. For the early modern period, this vast transmission and reception is indeed attested in a space between the Ottoman Balkans and the Indian Subcontinent, as becomes evident from both manuscript sources and printed editions. To give only two examples, for a discussion of the reception and translation of the Pandnāma in the Balkans, see Drkić/Reisi: “Dalāyil va ās̱ār-i ravāj-i Pand-nāma-yi mansūb ba ʿAṭṭār dar Būsnā”; for a discussion of a translation into Urdu, see Zweng: “Pandnama: Kritische Textausgabe und Übersetzung der Urduinterpretation des klassischen persischen Lehrgedichtes Pandnama”.

[4] On different modes of reading for such Persian classics in the Ottoman context, see İnan: “Ottomans Reading Persian Classics”.

[5] For overview of the translations and commentaries produced on the basis of the Pandnāma, see Yazar: Anadolu Sahası Klâsik Türk Edebiyatında Tercüme ve Şerh Geleneği, pp. 376-397.

[6] On the attribution to this author, see Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, pp. 17-18.

[7] On the date of completion, see ibid, 19.

[8] Cited from MS Süleymaniye, İzmir 612, f. 2b. For the Latin-script edition, see Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, p. 24.

[9] While there are certain variations in the manuscript corpus of the work, these are the numbers as given by Azmi Bilgin in her Latin-script edition. For an overview of the chapters, see Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, pp. 21-24.

[10] Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, p. 21.

[11] Cited from MS Süleymaniye, İzmir 612, f. 29b. For the Latin-script edition, see Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, p. 128.

[12] For the catalogue entry of the manuscript, see Dashian: Catalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Mechitharisten-Bibliothek, p. 18.

[13] The transliteration scheme employed in this blog entry conforms with the standards outlined in Çelik/Sargsyan: “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies”.

[14] The titles are rendered in the Bolorgir or cursive script.

[15] On the usage of “ե” (y) after consonants in Arabic and Persian words in the Armeno-Turkish script, see Çelik/Sargsyan: “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies”, pp. 175-176 and Ambros/Çelik/Sargsyan: “Intertwined Literatures: Karamanlı, Armeno-Turkish, and Regular Ottoman Versions of the Köroğlu Folktale”, pp. 31-32.

[16] Cf. the present orthography to the one found in Armeno-Persian works as presented in Kirakosyan: “The Orthographic Rules of the Eighteenth Century Armeno-Persian Gospels of the Matenadaran”.

[17] Cited from MS Süleymaniye, İzmir 612, f. 1b. For the Latin-script edition, see Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, p. 29. The second hemistich of the second verse here constitutes a variant.

[18] Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, p. 103.

[19] On this notion in the context of Armeno-Turkish translations and Chrisitan juvenile literature, see the blog post by Hülya Çelik and Ani Sargsyan titled “Christoph von Schmid in the Ottoman Literary Landscape: Armeno-Turkish Translations and the Shaping of Christian Juvenile Literature” in this blog.

[20] In the edition, āzādī instead of āzād is given. See ibid., p. 49.

[21] The chapters are given in Bilgin: Terceme-i Pendnâme-i ‘Attâr, pp. 37-39.

[22] Dashian: Catalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Mechitharisten-Bibliothek, p. 18. The entry in the catalogue also mentioned two small writings (on fols. Ib and 55b) mentioning the name “Giovanni” and “Giovantov”.

[23] Paşayan: Miftāhü’l-ʿulūm, p. 2.

[24] The study of the present manuscript and a survey of further Armeno-Turkish and Armenian versions of the Pandnāma is ongoing and more insights in this respect are to be published in the near future.