Nevra Lischewski (Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich)

The Ottoman Empire was celebrated for its linguistic diversity, encapsulating a complex interplay of languages that shaped its sociolinguistic profile. Central to understanding this multilingualism is the phenomenon of Armeno-Turkish, which involved writing the Turkish language using the Armenian script. This phenomenon offers a unique vantage point for examining the intricate linguistic relationships within the empire through a contemporary linguistic lens. This essay intends to position Armeno-Turkish as a distinct linguistic phenomenon by harnessing various concepts, terms, and approaches from contemporary linguistic disciplines. I aim to construct a theoretical framework that not only situates Armeno-Turkish within its rightful linguistic context but also provides a nuanced interpretation of its development and function. At the heart of this endeavor are several key concepts and terms, among which the ‘Sociolinguistic Profile’ stands as our initial point of focus. This term, along with others selected from contemporary linguistic disciplines, will guide our exploration, offering a framework through which to analyze the complex interplay of languages in the Ottoman Empire. Through this lens, we will examine how Armeno-Turkish interacted with, influenced, and was shaped by the surrounding sociolinguistic environment, providing insights into its emergence as a unique tool for cross-cultural communication.

Building the Linguistic Framework

Armeno-Turkish is a linguistic construct suggests that it developed through a process of synthesis. Thus, a thorough linguistic analysis of this entity necessitates an examination of the broader linguistic milieu within which it is embedded, positioning it as an integral component of this environment.

For the linguistic analysis of Armeno-Turkish, I have selected the sociolinguistic term sociolinguistic profile to encapsulate the entirety of the context in which Armeno-Turkish is situated. The sociolinguistic profile furnishes detailed linguistic information about the various languages that coexisted during a specific period within a defined region, thereby elucidating key sociolinguistic dimensions of multilingual settings.[1] Given the multilingual nature of the Ottoman Empire, it is rationally justified to employ this term to gain insight into the complex dynamics and interactions among the various linguistic communities within the empire.

Constructing a sociolinguistic profile is a challenging endeavor. Despite the existence of various approaches and methods[2] to achieve this, I wish to discuss the approach I have pursued. My methodology progresses along three interrelated yet distinct trajectories. Initially, my research focused on the linguistic landscape, a term that encompasses the visible and audible presence of languages within various personal, social, and cultural spheres.[3] This involved examining past linguistic landscapes through the written expressions found on artefacts such as ceramics, bottles, boxes, banknotes, coins, manuscripts, printed materials, and inscriptions on tombstones and monuments. The written expressions on those artefacts not only illustrate the linguistic diversity of the Ottoman Empire but also underscore its recognized multilingualism. However, recognizing the Ottoman Empire as multilingual only begins to describe its complex societal dynamics. Multilingualism is not merely a descriptor but a dynamic force that shapes society in productive ways, exhibiting qualities beyond mere linguistic diversity.

To deepen the understanding of multilingualism, I have turned to the field of Linguistic Ecology, which examines the complex interactions between languages and their environments. Central to this ecological approach is the understanding of language as part of complex socio-historical-cultural systems, with different dimensions and levels interacting.[4] The interactions within a language’s social environment, including its varieties and coexisting languages, define and shape it, much like natural ecological systems are structured and defined by functional interconnections between their inhabitants and their respective environments.[5]

The emphasis that linguistic ecology places on the multifaceted and dynamic nature of language provides a holistic perspective for analyzing multilingualism. At this stage, I employ the term linguistic mediator, which I propose for the description of the strategies and behaviors of coping with the complexity of multilingualism.[6] Such linguistic mediators are being used in the sociolinguistic landscape to manage the communication between different language varieties or languages. Resulting from practical needs, they play a crucial role in the transfer of knowledge as well as in cultural and linguistic exchange.

In the following, I will present examples of different kinds of linguistic mediators within the sociolinguistic context of the Ottoman Empire.

Linguistic Mediators in Action within the Sociolinguistic Profile of the Ottoman Empire

Through the lens of linguistic ecology, the Ottoman Empire emerges as a dynamic backdrop where various linguistic components interact. In this multilingual context, Turkish served as both the vernacular and the native or second language for many within the speech community. It functioned as the language of wider communication, or lingua franca, predominantly used in the public sphere across large portions of the late Ottoman Empire.[7]

Turkish, as a common language or lingua franca, can be considered a linguistic mediator in both spoken and written forms, facilitating daily interactions among diverse linguistic communities. The primary function of a common language is to enable smooth and uncomplicated communication between different groups in contact situations.

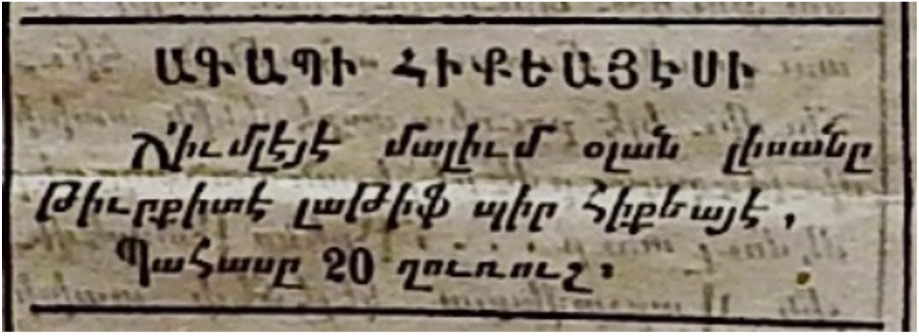

The Turkish language journal Mecmua-i Havadis (Journal of Events), which was printed with Armenian Script, featured the advertisement of the Turkish novel Akabi Hikayesi [8] (The Story of Akabi (Figure 1))[9] in the middle of its last page: AKABİ HİKAYESİ Cümleye malum olan lisan-ı Türkçe’de latif bir hikaye, bahası 20 Guruş (STORY OF AKABI A pleasant story in Turkish as a common language for everybody.)” The announcement referred to the Turkish language as “…[C]ümleye malum olan lisan” (Language known to everybody).

Figure:1 Advertisement of the first Turkish novel Akabi Hikayesi

The fact that a novel by an Armenian author was written in Turkish using the Armenian Script, and the emphasis this received in advertisements, serves as evidence of the accessibility and comprehensibility of Turkish for all speech communities of the Ottoman Empire. This demonstrates how Turkish functioned effectively as a linguistic mediator, bridging diverse linguistic groups and facilitating cultural and linguistic exchange. Interestingly, the newspaper advertisement itself supports this argument, as it is written in Turkish but uses Armenian letters, published in a newspaper where the language is Turkish and the script is Armenian. The alignment of form and content in the advertisement not only underscores the widespread understanding of Turkish but also highlights the innovative linguistic processes at play. The primary function of a common language is to facilitate smooth and uncomplicated interaction between different groups in contact situations. Additionally, it serves as a catalyst for innovation, introducing new linguistic outcomes into the sociolinguistic profile through the contributions of various linguistic communities. In this context, such innovation occurs through multigraphization, which is the next example as a linguistic mediator. Multigraphization, also known as allography, is the simultaneous use of several writing systems for the same language.[10]

Next, I will explore the phenomenon of multigraphization in Turkish, a noteworthy result of interlingual interaction. Multigraphization, as a linguistic mediator, entails the use of multiple scripts for a single language. This practice emerged out of practical necessities and significantly contributed to the transfer of knowledge as well as cultural and linguistic exchanges among diverse groups. [11] The extent of these exchanges varied, influenced by the differing levels of linguistic competence and contributions from various groups. Armenians, often bilingual, typically had greater familiarity with Turkish than Greeks, resulting in a higher prevalence and readership of Turkish texts in Armenian script compared to Turkish with Greek Script.

Nonetheless, all instances of multigraphization are equally important as linguistic mediators, regardless of the differences in Turkish proficiency and the volume of multigraphic production. Writing Turkish in Hebrew script, for instance, should also be regarded as a linguistic mediator. This practice emerged as a pragmatic solution to help the Jewish population of the empire learn Turkish more efficiently, thus ensuring effective communication among diverse linguistic communities.

Multigraphization facilitated cross-linguistic encounters and subsequently shaped the Ottoman Empire’s linguistic landscape. Evidence of this can be found in literary and scholarly works, newspapers, journals, and books. Initially, it might seem that multigraphization primarily benefited the groups who adapted their familiar scripts to the Turkish language. For example, the use of Armenian script for Turkish might appear to serve only Turkish-speaking Armenians. However, multigraphization proved to be a robust linguistic mediator, gradually increasing its influence across various linguistic groups. The interest in the multigraphic written corpus spurred the production of scholarly works and script guides, which functioned as additional linguistic mediators by introducing Turkish in different scripts to a broader audience. The subsequent examples will illustrate such linguistic mediators.

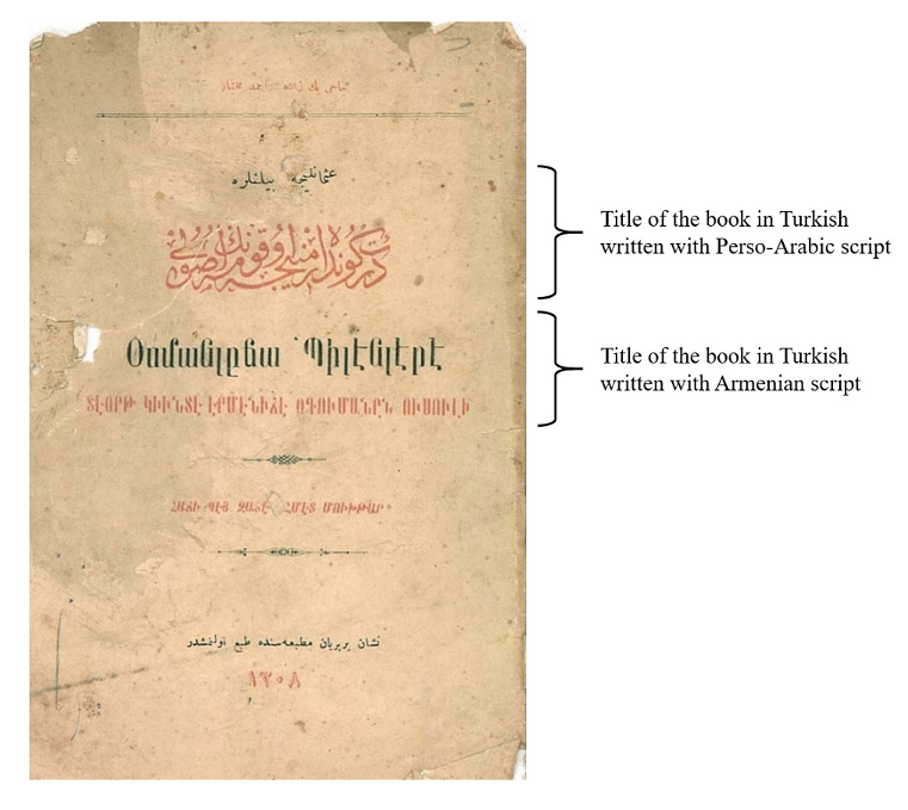

The guide ʿOs̱mānlıca Bilenlere Dört Günde Ermenīce Oḳumanıñ Uṣūlī [12] (The method of Reading Armenian in Four Days for Those who Know Ottoman), authored by a Muslim author, Ḥacı Beg Zāde Aḥmed Muḫtār in 1890, was designed to teach the Armenian Script (see, figure 2). Notably, this guide was written by a Muslim author, which challenges the assumption that the use of Armenian script for Turkish solely served Armenian speakers.

Figure 2: Title page of ʿOsmānlıca Bilenlere Dört Günde Ermenīce Oḳumanıñ Uṣūlī

In this work, the author developed seventeen practical rules to teach the Armenian Script, introducing its written symbols alongside the phonemes they represent and the corresponding Perso-Arabic symbols. This method was also applied in reverse; the Perso-Arabic script was described based on the phonetic features of the Armenian script system (see, Figure 3)[13]. The author illustrated both printed and handwritten forms of the Armenian script, demonstrating his proficiency with the phonetic systems of both languages.

The title of this work and the introductory remarks reflect the author’s confidence in the ease of learning the Armenian script. He assures readers that with consistent practice, they could proficiently read Armenian letters within a few days, provided they follow the lessons sequentially: “… I assure you that if you are occupied with practicing that book as long as your schedule allows you, in a couple of days you will be able to read the Armenian letters very well. However, under the condition that you will do the lessons one after another …”[14]

Additionally, the author highlights the extensive range of printed materials available in Turkish using Armenian script and the interest these publications garnered among different groups: “This book can show the easiest way to read for the ones who wants to read the news- papers, illustrated weekly periodicals, novels and etc., which are in Turkish and written in Armenian script. However, this book can also be a guide for the one whose language is Armenian.”[15]

Furthermore, there are other instances of adopting different scripts for the languages of the Ottoman Empire. For example, a booklet from 1861 introduced the Kurdish language in Armenian Script and was published in Armenian and Kurdish with Armenian script. Several translations of the Bible and other books into Kurdish with Armenian script were printed in Istanbul between 1856 and 1911.[16] Writing one language in multiple scripts or writing texts using the script of another language was extremely common from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century.

The acceptance of different scripts in the public sphere significantly influenced the linguistic landscape. This is evidenced by multigraphic street signs, business cards, shop labels, operetta theatre posters, and tags for daily consumer products such as cigarettes, matchboxes, shoeboxes, medicine, marmalade, liquor and perfume bottles, toothpaste, and wrapping paper.

As we have explored the multifaceted linguistic practices and the role of linguistic mediators within the Ottoman Empire, it becomes evident that these dynamics were integral to the empire’s multilingual and multicultural fabric.

Final Reflections

Utilizing linguistic ecology and various terminological concepts developed across linguistic fields, this research has aimed to decipher the complex linguistic interactions within the empire, with a particular emphasis on the phenomenon of Armeno-Turkish.

One significant finding from this analysis is the pivotal role of Turkish as both the major language and vernacular, fulfilling multiple functions including wider communication and official duties. The exploration of Turkish as a common language revealed a comprehensive, long-term process involving various societal segments. This dynamic development was not isolated but interconnected with the efforts of Armenians, Greeks, and Jews, who played a crucial role in the emergence of the written vernacular Turkish through multigraphization.

The practice of multigraphization, especially the use of Armenian script for writing Turkish, serves as a prominent example of linguistic mediation. This adaptation was not just a pragmatic response to communication needs but also a strategic effort to foster easier learning and integration among different linguistic communities, particularly highlighted by the widespread publication of materials like Mecmua-i Havadis. The utilization of Armenian script in Turkish publications underscores the integrative and inclusive nature of the Ottoman linguistic landscape, challenging the notion that such practices served only the Armenian community.

Furthermore, the presence of multigraphic elements in public spaces—from street signs to product labels—illustrates the societal acceptance and functional significance of multiple scripts, reflecting the dynamic interplay of languages and scripts across various domains. This acceptance facilitated not only linguistic but also cultural exchanges, contributing significantly to the sociolinguistic profile of the Empire.

Through the lens of linguistic ecology, this paper has examined the dynamic interactions between coexisting languages and their communities, conceptualized as cross-linguistic encounters. These interactions, often innovative and productive, have led to the development of “linguistic mediators.” These mediators, whether in the form of languages, scripts, or cultural artifacts, emerged from practical needs and significantly influenced the transfer of knowledge and cultural exchange within the empire.

In synthesizing these findings, the term “sociolinguistic profile” has been redefined to reflect a dynamic scene characterized by the constant interactions of languages and speakers, with Armeno-Turkish playing a central role. These interactions, facilitated by linguistic mediators, ensure that all components of the multilingual landscape remain vital and capable of generating new linguistic outcomes.

Ultimately, this paper not only highlights the complex nature of multilingualism in the Ottoman Empire but also emphasizes the transformative impact of Armeno-Turkish as a linguistic mediator. The insights gained here encourage a broader appreciation of multilingualism’s role in shaping dynamic and productive societal processes and offer a model for analyzing other multilingual settings.

Bibliography

Fasold, Ralph. “Naturalism and the Search for a Theory of Language Types and Functions.” in Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties, ed. Ulrich Ammon (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1989), 107-21.

Ferguson, Charles A. “National Sociolinguistic Profile Formulas.” Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of UCLA Sociolinguistic Conference, (1964): 309-24.

Haarmann, Harald. “Language Planning: Graphization and the Development of Writing Systems,” in Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of Science of Language and Society, Vol. 3, eds. Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier, Peter Trudgill (Berlin: Walter de Gruyder, 2006), 2402-20.

Hacı Bey Zade Ahmed Muhtar, ʿOs̱mānlıca Bilenlere Dört Günde Ermenīce Oḳumanıñ Uṣūli (İstanbul: Nişan Berberyan Matbaası, 1890).

Haugen, Einar, “The Ecology of Language,” in Ecolinguistic Reader: Language, Ecology andEnvironment, ed. Alwin Fill and Peter Mühlhäusler (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2006), 55-106.

Landry, Rodrigue and Bourhis, Y. Richard. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study”, Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 16, no.1 (1997): 23-49.

Lischewski, Nevra. From Multilingualism to Monolingualism: Sociolinguistic Profile and Language Planning in the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey (1850–1950) (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2022).

Ludwig, Ralph, Pagel, Steve and Mühlhäusler, Peter. “Linguistic Ecology and Language Contact: Conceptual Evolution, Interrelatedness, and Parameters,” in Linguistic Ecology and Language Contact, eds. Ralph Ludwig, Steve Pagel, and Peter Mühlhäusler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 3–42.

Malmîsanij, Mehemed, Türkiye ve Suriye’de Kürtçe Kitap Yayımcılığının Dünü ve Bugünü, ed. Deniz Gündüz (İstanbul: Vate Yayınevi, 2006).

Shohamy, Elana. “Linguistic Landscape after a Decade: An Overview of Themes, Debates and Future Directions,” in Expanding the Linguistic Landscape: Linguistic Diversity, Multimodality and the Use of Space as a Semiotic Resource, eds. Martin Pütz and Neele Mundt, (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2018), 25-37.

Stewart, William. “A Sociolinguistic Typology for Describing National Multilingualism,” in Readings in the Sociology of Language, ed. Joshua A. Fishman (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 1968), 531-45.

Tietze, Andreas, ed., Akabi Hikayesi: İlk Türkçe Roman (1851) (İstanbul: Eren Yayınları, 1991).

[1] The foundational concepts of the sociolinguistic profile were first developed in the 1960s by William Steward and Charles Ferguson, who sought to systematically describe and classify languages within multilingual societies. Ferguson, “National Sociolinguistic Profile Formulas.”; Stewart, “A Sociolinguistic Typology for Describing National Multilingualism,”.

[2] The limitations inherent in developing generalizations concerning sociolinguistic profiles as well as representing and applying them to different cases are mentioned by Fasold, “Naturalism and the Search for a Theory of Language Types and Functions,” 109-110.

[3] For the development of the of linguistic landscape and its emerging as a interdisciplinary area, see Shohamy, “Linguistic Landscape after a Decade: An Overview of Themes, Debates and Future Directions,” 25-27.

[4] For the definition of the term „Linguistic Ecology “, see Haugen, “The Ecology of Language,” 325.

[5] An outline of the developments and various perspectives in the discussions on linguistic ecology is provided by Ludwig, Mühlhäusler, and Pagel, “Linguistic Ecology and Language Contact,” 1-19.

[6] A detailed definition of linguistic mediators, along with additional examples, can be found in Lischewski, N. From Multilingualism to Monolingualism, 53-69.

[7] I applied the categories and types from Ferguson to examine the status of Turkish, utilizing his framework for categorizing individual languages within linguistic diversity. Ferguson’s approach involves categorizing languages into distinct types to analyze their roles within a multilingual context. Ferguson, “National Sociolinguistic Profile Formulas”.

[8] Vartan Paşa (Osep Vartanian; Armenian: Վարդան փաշա, 1813–1879) was an Ottoman official, author, translator, and journalist of Catholic Armenian origin in the 19th century. He authored the first known novel-like text in Turkish, the novella “Akabi’s Story” (Akabi Hikayesi), published in 1851. Although written in Turkish, the text used Armenian letters and appeared in the newspaper Mecmua-i Havadis. For the novella, Tietze, Andreas, Akabi Hikayesi: İlk Türkçe Roman.

[9] Mecmua-i Havadis, no. 21, Februar 13, 1854, 4.

[10] The term multiple graphization is used and explained with examples by Haarmann, “Language Planning: Graphization and the Development of Writing Systems,” 2406.

[11] It is worth noting that the general principles regarding the development and function of multigraphization discussed here can also be applied to the use of the Greek script and Hebrew script for Turkish. Although there are some nuanced differences, the overarching sociohistorical dynamics, and pragmatic adaptations for literacy in diverse communities follow a similar pattern. For a detailed analysis, see Lischewski, From Multilingualism to Monolingualism, 26-37; 57-65.

[12] Ḥacı Beg Zāde Aḥmed Muḫtār, ʿOsmānlīca Bilenlere Dört Günde Ermenīce Oḳumanıñ Uṣūlī.

[13] Ibid, 3.

[14] Ibid, 1.

[15] Ibid, 1.

[16] Malmisanij, Türkiye ve Suriye’de Kürtçe Kitap Yayımcılığının Dünü ve Bugünü, 34.