Yavuz Köse (University of Vienna)

Introduction[1]

The notable surge in interest in culinary topics is not just a recent phenomenon post-pandemic: countless cooking shows circulate across all channels; Netflix alone broadcasts a variety of documentaries and cooking shows about foods and beverages from around the world. Cookbooks are selling like hotcakes globally. For instance, if you search for “Turkish Cuisine” on the online sales platform Pandora, the platform lists more than 650 titles. Moreover, the market does not seem to have reached saturation.

Among all these, historical cookbooks have their unique charm, offering us perspectives not only in terms of recipes, ingredients, and preparation techniques but also on matters of “mentalities, customs, ideas, daily life, technological developments”. They assist in researching topics such as “culinary history, culinary development, table manners, and social differences”.[2]

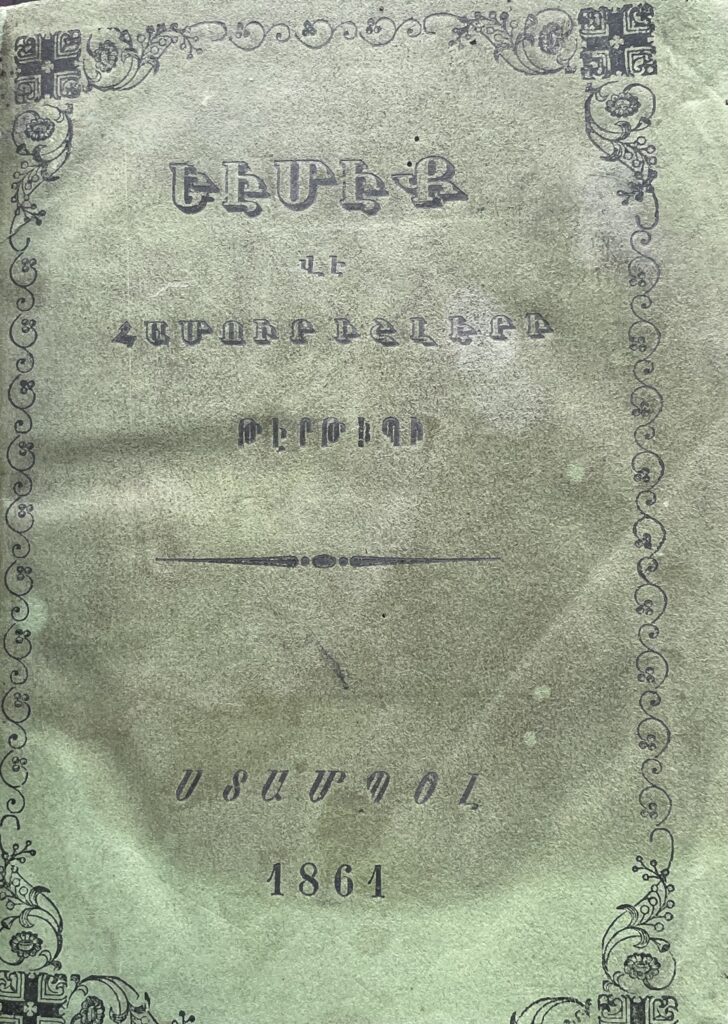

In this article, I aim to introduce a historically overlooked and intriguing cookbook: Yemek ve Hamur İşleri Tertibi [The Arrangement of Cookery and Pastries], published in 1861 in Istanbul. The book is in Turkish with Armenian letters, a script known as Armeno-Turkish. The cookbook addresses a notable gap in previous research on Ottoman/Turkish cookbooks and establishes new connections with existing culinary literature. Beyond complementing the extant body of work[3], the book facilitates an examination of the influence of Ottoman cookbook recipes on Armeno-Turkish books. Furthermore, it allows us to trace the impact of Armeno-Turkish cookbooks on those written in Ottoman Turkish.

Genealogy of Ottoman Cookbooks

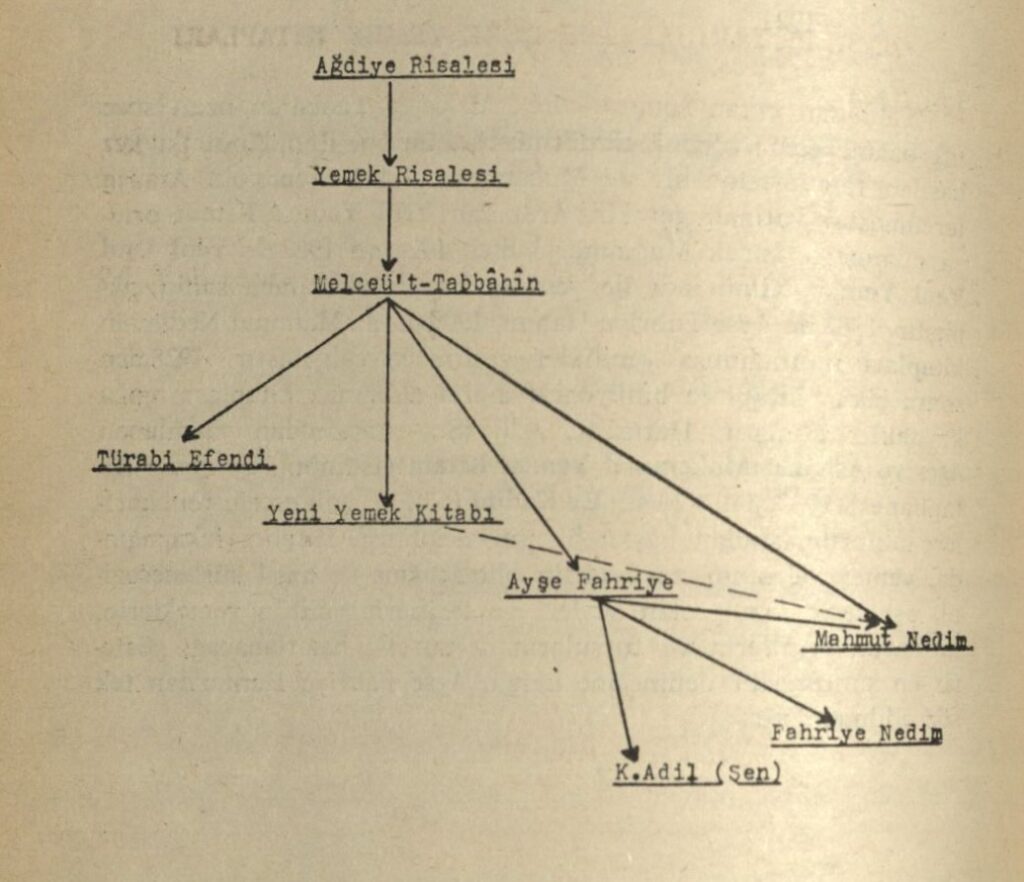

When Turgut Kut first undertook to systematically study Ottoman cookbooks and their interrelations in 1985, he proposed the following genealogy in his annotated bibliography on the subject:

Source: Turgut Kut, Açıklamalı Yemek Kitapları Bibliyografyası. Eski Harfli Yazma ve Basma Eserler. Ankara 1985, 22.

According to this, the cookbook titled Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn (The Shelter of Cooks), published in 1844, played a central role.[4] Although Kut hinted at the existence of Armeno-Turkish cookbooks, he did not delve into their relationship with other cookbooks in his genealogy. However, traces of this issue can be found in a master’s thesis completed in 2019. Ergen’s study briefly chronicles all known Ottoman recipe books alongside those written in Armenian letters, examining the relationship between these cookbooks by focusing solely on their table of contents sections. Ergen admits in her thesis that she included cookbooks published in 1861, 1871, and 1876 without having seen them in person, noting that she had indirect access to the table of contents section of the 1871 and 1876 publications.[5] She states that the contents of the 1871 publication were provided to her as a “list” and that she used an article by Turgut Kut (2009) that included the table of contents section of the same publication from 1876.[6] Besides a brief entry in Hasmik Stepanyan’s Bibliography of Armenian-Letter Turkish Books and Periodicals[7], Ergen found no information on the cookbook introduced here.

Comparative Analysis of Historical Cookbooks

When comparing the table of contents sections of the 1871 and 1876 editions, inconsistencies in the number and arrangement of recipes are observed. This is particularly striking for the cookbook published in 1871 titled Yeni Yemek Kitabı ve Hamur İşleri. Şimdiki Usuller ve Meşhur Aşçıların Kullandıkları Tertibler Üzerine (New Cookbook and Pastries. Current Methods and the Arrangements Used by Famous Chefs)[8]. The conclusions Ergen reached about a book she had not seen herself show differences from what we see in the actual “contents” section available today. For instance, there are inconsistencies in the number of recipes; Ergen mentions having a list with 180 recipes, yet the table of contents section we have lists only 150 recipes. Furthermore, the table of contents section is not disorganised; rather, it is divided into eight sections, including titles. The book also contains an introductory section explaining why the author wrote the book, unfortunately using only the initials T.V. instead of a full name. The introduction goes as follows:

As everything changes with time, so have the arrangements of dishes changed in the current era compared to twenty or thirty years ago, and it is for this reason that we have directly embarked on publishing this booklet; although a cookbook was printed previously, its arrangements did not match, making it unsuitable for current chefs, and because that previous cookbook was lacking in another sense of arrangement, we have added an index at the end of this book to facilitate finding the dishes as easily as possible. [9]

This takes us to the cookbook from 1861. A connection can seemingly be made from the titles of both books: Yemek ve Hamur İşleri Tertibi (İstanbul, 1861) and Yeni Yemek Kitabı ve Hamur İşleri. (İstanbul, 1871)

This connection becomes clearer in light of T.V.’s explanations in the introduction. In fact, the 1861 cookbook is disorganized – that is, recipes are not sorted into specific sections – and lacks a table of contents section, which would have naturally facilitated the reader’s navigation and use of the book, especially considering that recipes could easily be linked to the sections of the 1871 cookbook. An unfinished, handwritten, alphabetically arranged table of contents page was added to the existing edition, presumably to allow quick access to the recipes.

| Alafranga börek 69 Bitter almond 110 Persian pilaf 21 Quince desserts 60 Quince jam 52-53 Ashura 47 Quiet helva 44 Hunter’s kebab 60 Pear and apple compote 51 Syrup 56 Scorpion fish grill 90 Apricot and plum dessert 50 Creamy crunchy 75 Creamy kadayif 39 |

When comparing the two books, one can see that 96 out of the total 180 recipes in the 1861 edition also appear in the 1871 book. This corresponds to 64% of the 150 recipes in the Yeni Yemek Kitabı. Except for one dish, almost no recipes containing alcohol (especially wine) are found in the 1871 edition, and the use of pork fat is also omitted from the “Lahana Dolması” (“Stuffed Cabbage”) recipe in this book. In contrast, the Armenian-Turkish cookbook Miftahü’t-tabbahin (The Cook’s Key, 1876) contains many recipes involving pork and alcohol. Similarly, the last Turkish cookbook in Armenian letters, Mükemmel Yemek Kitabı (The Perfect Cookbook, 1926), does not include any pork recipes, but the section titled “Alafranga Style” contains recipes with wine and rakı.[10]

Let’s return to the relationship between Armeno-Turkish and Ottoman Turkish cookbooks. What is the connection between cookbooks published in 1861 and 1871 in Armenian letters and the oldest printed Ottoman Turkish cookbook from 1844? A comparison of the recipes in the 1861 book (180 recipes) with those in Mehmed Kâmil’s Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn (The Shelter of Cooks, 272 recipes) shows that 69 recipes have identical titles. This corresponds to 38% of the 180 recipes in the 1861 book. On the other hand, a comparison between the recipes in the 1871 book and Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn reveals 52 identical recipe titles, accounting for 35% of the total 150 recipes. Thus, it can be said that there are significant similarities between the recipes in the 1844 and 1861 books.

Another interesting point is the resemblance of the 1871 Armeno-Turkish cookbook to an Ottoman Turkish cookbook first printed in 1880: Yeni Yemek Kitabı. Şimdiki Usuller ve Meşhur Aşçıların Kullandığı Tertipler Üzere bi-Nazır Ta’amların Tertibatı (Current Methods and the Arrangements Used by Famous Chefs Regarding the Preparation of Unique Dishes).[11] Not only the titles but also the table of contents of the two books are nearly identical in content and structure. Ergen’s study does not make this connection because it was conducted using a “contents” section that was not original and, unfortunately, could not realizethat the 1861 Armeno-Turkish cookbook served as a model for the 1871 edition.

Comparing the 1861 and 1871 cookbooks with the 1876 Miftahü’t-tabbahin, only 28 out of 180 recipes (about 16%) from the earlier editions are found in Miftahü’t-tabbahin (which contains 750 recipes), representing less than 4% of the recipes in the later publication. In the Yeni Yemek Kitabı (1871, with 150 recipes), we find a total of 32 recipes. These recipes make up about 4% of the 750 dishes in Miftahü’t-tabbahin and 21% of the 1871 cookbook. Therefore, we can say that only a small portion of the recipes from the 1861 and 1871 cookbooks appear in Miftahü’t-tabbahin. The same applies to the recipes in Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn.

Now, let’s make a comparative analysis in terms of content. For this comparison, I have selected recipes found in the cookbooks dated 1844 (Ottoman), 1861 (Armeno-Turkish), 1871 (Armeno-Turkish), 1876 (Armeno-Turkish), and 1882/1894 (Ottoman).

An examination of the recipe texts in this context reveals interesting connections:

The descriptions in the recipes that appear in both the 1861 and 1871 editions are almost identical, with only minor stylistic differences. Other recipes show a more intense editorial hand in terms of style.

Although only about 35% of the recipes from the 1844 and 1861 publications match, the recipes in both books show significant similarities.

| Yemek ve Hamur İşleri Tertibi, 1861 | Melceü‘t Ṭabbāḫīn, 1844 |

| Pirinc paḳlavası (Rice baklava) | |

| Bir ölçü erimiş ve köpüyü alınmış bal; ve bir ölçü erimiş yaġ; ve bir ölçü su, ve bir ölçüden az ziyade pirinc unu ve bir fincan durulmuş küllü su; bu cümlesini bir tencireye ḳoyub ateş üstünde kebçe ile ḳarıştıraraḳ temam helva gibi ḳoyu olduḳda bir tepsi içine kepçe ile yalıb furunda pişirmeli; eyice ḳızardıḳda paklava gibi kesib şeker ekmeli. | Bir ölçü erimiş ve köpüğü alınmış asel ve bir ölçü erimiş rûgan-ı sâde ve bir ölçü su ve bir ölçü torukluca pirinç unu ve bir fincan durulmuş keskince küllü su . Cümlesini bir tencereye vaz birle ateş üstünde kepçe ile karıştırarak tamam helva gibi koyuldukta bir tepsi içine kepçe ile yayıp fırında tabh oluna iyice kızardıkta çıkarıp baklava şeklinde kesip üzerine şeker ekip tenâvül buyrula. Asel bulunmaz ise kıvamlıca şeker istimal oluna. |

| A measure of melted and skimmed honey; and a measure of melted butter; and a measure less than a measure of rice flour and a cup of clarified lime water; mix all these in a pot on the fire, stirring with a ladle until it thickens like halva, then spread it with a ladle into a tray and bake in the oven; when it has browned well, cut into baklava pieces and sprinkle with sugar. | Mix a measure of melted and skimmed honey, a measure of melted plain butter, a measure of water, a measure of finely ground rice flour, and a cup of clarified lime water. Combine all in a pot and mix with a ladle over the fire until it thickens like halva, then spread in a tray with a ladle and bake in the oven until well browned, then remove, cut into baklava shapes, sprinkle sugar on top, and serve. If honey is not available, use thick sugar. |

While the Ottoman version frequently employs Persian compound structures, these are not used in the Armenian-letter Turkish version; aside from this, the amounts and ingredients are nearly identical.

Looking closely at the recipes in the 1871 edition, we can establish a direct connection to the Ottoman Turkish New Cookbook first published in 1880 and subsequently reprinted three times.[12] The language of the recipes in the 1871 Armeno-Turkish book is almost identical to that of the Ottoman Turkish cookbook. Comparing the two books reveals that the Ottoman version was likely directly transferred from the Armeno-Turkish edition. As shown earlier, even the introduction to the Ottoman cookbook, with a few minor differences, is the same.

| Yemek ve Hamur İşleri Tertibi, 1861 | Yeni Yemek Kitabı ve Hamur İşleri. Şimdiki Usuller ve Meşhur Aşçıların Kullandıkları Tertibler Üzerine (1871) | Yeni Yemek Kitabı Şimdiki uṣūller ve meşhūr aşçılarıñ ḳullandıġı tertībler üzre bī-neẓīr ṭaʿāmlarıñ tertibātı (1882/83) |

| Gözleme | ||

| Ḫamuru bir kaç yumurta ile say yaġilen gereyi gibi yoġurduḳdan soġra üç tabaġa açıb aralerine yaġ sürerek biri birinin üzerine ḳoymalı ve kyaġad büker gibi büküb parça parça keserek yaġı dişarı gelmemek içün uclarını sıkıb kesilmiş tarafından avucunın içinde yassıladıb merdane ile açdıḳdan songra iḳtiza eden içi ḳoyub iki ḳat idub üzerine yumurta sarisını sürerek furuna vermeli. | Hamuru bir ḳaç yumurta, ve say yaġı ile yoġurub terki terki edib aralarına yaġ sürerek üst üste ḳomalı, badehu evvela merdane ile ve sonray oḳlavu ile incecik açıb içine yaġ serṗmeli, ve o yufḳayı üç dört ḳat birbir üstüne ḳavuşdurub ḳararca kesmeli, ve tavada ḳızġın yaġ içinde pişirmeli. Bunun peynirlisi yaḫod ḳıymalısı daḫi olabilir. | Ḫamurı birkaç yumurṭa ve ṣaġ yaġıla yoġurup terki terki ėdüp aralarına yaġ sürerek üst üste koymalı baʿdehu merdāne ile ve ṣoñra oklava ile ince açup ince yaġ serpmeli ve ol yufkayı üç dört kat birbiri üstüne kavuşdırup kararca kesmeli ve ṭavada kızġın yaġ içinde pişürmeli bunıñ peynirlisi yāḫūd kımalı daḫī olabilir |

| After kneading the dough with a few eggs as necessary, roll it out into three layers, spreading butter between each layer, stacking them, rolling like a scroll, cutting into pieces, pinching the ends to keep the butter from escaping, flattening with the hand and then rolling out with a rolling pin, placing the required filling, folding into two layers, brushing with egg yolk, and baking in the oven. | Knead the dough with a few eggs and as much butter as needed, layer by layer, spreading butter between layers, then stack them on top of each other. After rolling out first with a rolling pin and then with a thinner rolling pin, spread thin butter on it, fold the dough three or four times on top of each other, cut into size, and fry in a pan with hot butter. It can also be made with cheese or minced meat. | Knead the dough with a few eggs and the right amount of butter, layer by layer, spread butter between the layers, stack them, then roll out with a rolling pin, and finally with a thinner rolling pin, spread thin butter, fold the dough three or four times on top of each other, cut into size, and fry in a pan with hot butter. It can also be made with cheese or minced meat. |

Conclusions

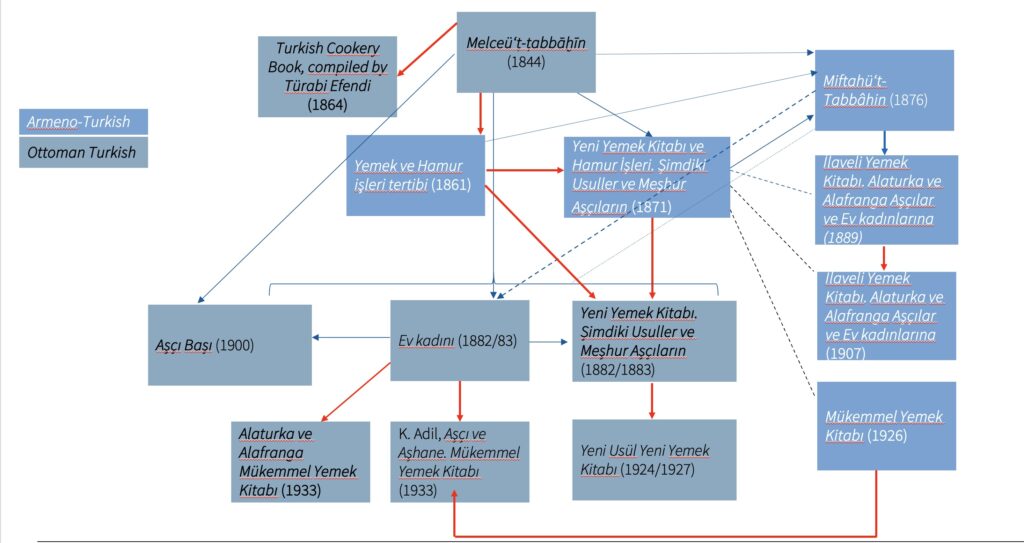

Now, it is time to reconsider Turgut Kut’s proposed genealogy of Ottoman cookbooks by incorporating the Armeno-Turkish cookbooks discussed in this study. This inclusion significantly expands Kut’s genealogy, revealing a more intricate and interwoven relationship between the culinary traditions recorded in Ottoman Turkish and those in Armenian letters. This expanded genealogy offers a more comprehensive understanding of the historical development of Ottoman culinary literature.

The examination of Yemek ve Hamur İşleri Tertibi (1861) highlights the significant yet overlooked role of Armeno-Turkish cookbooks in the culinary literature of the Ottoman Empire. This cookbook fills a gap in the historiography of Ottoman/Turkish cookbooks and establishes critical connections between various culinary texts across different languages and scripts. By comparing the recipes and content with other historical cookbooks, it becomes evident that there was substantial interaction and mutual influence between cookbooks written in Ottoman Turkish and those in Armenian letters. Finally, considering Hovhannes Karnetsi’s work on an extensive cookbook including Armenian and Ottoman dishes in Istanbul during the 1820s, it becomes evident that the history of Ottoman cookbooks will always remain incomplete without incorporating such texts into research. [13]

[1] I would like to sincerely thank Fr Simon Bayan, the librarian in charge of the Library of the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna, for the opportunity to review the book. Many thanks also to Ani Sargsyan and Hülya Çelik for their support and corrections. A Turkish version of my prestantion at the Turkologentag 2023 has been published in Yemek ve Kültür 75,1 (2024): 60-66. The cookbook will be published by Aras Publishing House in 2025.

[2] Henry Notaker, A History of Cookbooks. From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries (Oakland, California 2022), ix.

[3] Turgut Kut, Açıklamalı Yeme Kitapları Bibliyografyası. Eski Harfli Yazma ve Basma Eserler (Ankara: Feryal Basımevi,1985), and Turgut Kut, “A Bibliography of Turkish Cookery Books up to 1927”, in Turkish Cuisine, ed. Arif Bilgin, Özge Samancı (Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2008), 329-337; Sidar, Ergen, Son Dönem Osmanlı Yemek Külütüründe Ermeni Mutfağının Katkısı: Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Yemek Kitapları (İstanbul: Libra Kitap, 2019); Özge Samancı, “Osmanlı ve Cumhuriyet Dönemlerinde Yemek Kitapları”, Anatolia: Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisim, 31,2 (2020): 205-210.

[4] Mehmed Kâmil, Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn. Aşçıların Sığınağı (İnceleme – Metin – Tıpkıbasım), eds. Günay Kut and Turgut Kut (İstanbul: T.C. Türkiye Yazma Eserler Kurumu, 2015).

[5] Ergen, Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Yemek Kitapları, 62-65.

[6] Turgut Kut, “Aşçılarn Anahtarı-Miftahü’t-Tabbâhîn”, Yemek ve Kültür 17 (2009): 119-127.

[7] Hasmik Stepanyan, Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Kitaplar ve Süreli Yayınlar Bibliyografyası (1727-1968) (İstanbul: Turkuaz Yayınları, 2005, 118.

[8] [T. V.], Yeni Yemek Kitabı ve Hamur İşleri. Şimdiki Usuller ve Meşhur Aşçıların Kullandıkları Tertibler Üzerine (İstanbul: Tabhaneyi T. Dividcyan, 1871).

[9] [T. V.], Yeni Yemek Kitabı ve Hamur İşleri. Şimdiki Usuller ve Meşhur Aşçıların Kullandıkları Tertibler Üzerine (İstanbul: Tabhaneyi T. Dividcyan, 1871).

[10] Vağinag Pürad, Mükemmel Yemek Kitabı 1926 (İstanbul: Aras, 2010), 175-6, 178, 184, 188.

[11] Özge Samancı, Yeni Yemek Kitabı (İstanbul: Yemek ve Kültür, 2016).

[12] Samancı, Yeni Yemek Kitabı.

[13] Greta Grigoryan, Գրետա Գրիգորյան, «Հայ խոհանոցին նվիրված Հովհաննես Ամիրայան-Մամիկոնյան Կարնեցու աշխատությունները», Լրաբեր հասարակական գիտությունների, հմր․7, Երևան, Հայկական ՍՍՀ ԳԱ հրատարակչություն, 1986, էջ 70-74 (Greta Grigoryan, “ The works of Hovhannes Amirayan-Mamikonian dedicated to Armenian cuisine”, Herald of Social Sciences 7 (1986): 70-74).