Hülya Çelik (Ruhr University Bochum) and Ani Sargsyan (University of Hamburg)

Introduction

Detailed comparative studies of the multidimensional nature of translations, particularly those in Armeno-Turkish, provide fresh perspectives on the diverse Ottoman literary landscape of the second half of the nineteenth century. This article draws on concepts such as “between two stools,” “Christian Turkish literature,” and “Turkish Kulturchristentum” (proposed by Johann Strauss and Laurent Mignon) to explore the transregional and inner-Ottoman translation trajectories of Armeno-Turkish literature. By examining two selected translations of Christoph von Schmid’s (1768-1854) works, this study explores the ecologies of translation, highlighting the significance of translation in the mobility and appropriation of ideas and texts.

A transimperial approach to translation and multilingualism broadens the scope beyond the dominant religious tradition of Islam and its “three languages” (elsine-i s̱elās̱e), as commonly emphasised in Ottoman studies. This approach enables a deeper exploration of the multireligious context within the Ottoman Empire and beyond, shedding light on common patterns regarding the significance of sacred languages across various religious communities. It examines the relationship between these sacred languages and vernaculars, the intricacies of translating between them, and the challenges of rendering religious texts into vernacular or foreign languages, printed forms, and different scripts.

Being “in-between” or “fallen between two stools,” Armeno-Turkish novels and other genres—translations as well as original works—have never found a place in Armenian or Turkish literary canons. However, the extensive presence of Armeno-Turkish printed material suggests this phenomenon was not extraordinary “exotic” for its time. Instead, it reflects the commonplace existence of cross-cultural contact zones in late Ottoman cities such as Istanbul, Smyrna/Izmir, Aleppo, and Jerusalem.[1] This literature demonstrates the complex interplay of languages and broader cultural interactions within the late Ottoman period.[2] Building on Laurent Mignon’s insights, this paper seeks to uncover a shared cultural heritage, echoing Hrant Dink’s concept of ‘the common memory’ of the Turkish and Armenian people.[3] By considering the concepts of Christian Turkish (Turco-Christian) literature[4] and “Turkish Kulturchristentum”,[5] and viewing Armeno-Turkish not merely as a dialect but as a functional style,[6] we highlight its role in the broader landscape of Ottoman multilingualism, examining its impact alongside Ottoman Turkish and Western Armenian literary works.

The flourishing of Armeno-Turkish literary production in the nineteenth century was significantly supported by Armenian printing houses in key Ottoman cities and the Mkhitarist printing houses in Europe (Vienna, San Lazzaro, Trieste). This network facilitated the dissemination of European literary works, including those by Christoph von Schmid, a prominent figure in eighteenth-century German literature known for his juvenile and devotional narratives (fromme Literatur). Schmid’s works resonated deeply across various Ottoman communities, emphasizing the broad appeal and cultural impact of Armeno-Turkish translations, which often preceded their Ottoman Turkish and Armenian versions.

This paper shows how these translations influenced Armeno-Turkish language and mixed cultural identities, revealing intricate translation practices and broader cultural implications. By analysing Christoph von Schmid’s works in translation, this paper aims to enhance our understanding of the complex web of translation, adaptation, and cultural transmission within the Ottoman Empire.

Genovefa – Genevieve – Yenoveva

The first and perhaps most cherished story examined in this context, which captivated both European readers and resonated within the Ottoman Empire, particularly among the Christian population, is Genovefa. This tale, based on the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, was rewritten in German by Christoph von Schmid and first published in 1810.[7]

The narrative had a widespread popularity throughout the Ottoman realm.[8] The story was evidently so well-loved that it was adapted into all three scripts—Greek, Armenian, and Arabic—used by Turkish-speaking and reading Ottomans of the time.[9]

The Armeno-Turkish translation of Yenoveva is attributed to an unknown translator, first published in 1855 and again in 1868 by the printing house of Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan in Istanbul.[10] Subsequent editions followed in 1890 and 1891, the latter printed by the Kavafyan printing house.[11] The preface (dibace) of the second edition, likely authored by Kürkcyan himself, hints at dissatisfaction regarding the delayed release, which took 13 years to produce 500 copies. Kürkcyan even adopts a tone of sarcasm, jesting that this second edition would probably endure until the end of his life, as expressed in the following passage:

…As it is the knowledge of the experts of reading [and] this story of ours had been printed once before and sold out …, Given that some enthusiasts have expressed a desire to read it, it has been deemed appropriate and fitting to print it again, this time without hesitation, in a neat and clean edition. However, we regret to say that while the first printing was in 1855, the second could only be done in 1868. That is, in exactly thirteen years, our little book could only be circulated with great difficulty in five hundred copies. And this time, it is beyond doubt that it will take just as long, meaning it can send us off to the other world. There is no doubt that the third printing will either be done by those who come after us, or we might do it upon our return […].[12]

The Karamanlidika version first appeared in 1854, translated by Evangelinos Misailidis and printed by the Anatoli publishing house, with a second edition printed between 1860 and 1870.[13] An Ottoman Turkish translation surfaced in 1868, attributed to Tatyos Dividjyan’s printing house and translated by Mehmed Memduh Paşa, the Minister of the Interior.[14] Some secondary sources mistakenly claimed that the original was written by Lamartine; however, this is incorrect.[15] Memduh Paşa’s translation was published only once, likely due to its “strange” and complicated Ottoman style of language.[16] Additionally, the story of Genevieve was also known to the Arab-reading public, likely translated from a French edition.[17]

The Armenian-speaking population also had access to this popular story. In 1849 (and subsequently in 1858, 1872, and 1900), the Mkhitarist Father of Venice, Vrtanes Buduryan, translated it into Armenian as History of Genovape, Duchess of Britain.[18] A rhymed Armenian version was translated into Armeno-Turkish by Mihran Arabacyan (d. 1898) in 1886 under his pen name Bidar, published by the Kavafyan printing house and entitled Ḳenovape nam Afıfe Ḳadının Hikyayei Ġaribesi, İngiltera Düşesalerınden.[19] Dikran-Haroutiun Dedeyan (1832-1868),[20] a prolific translator and publisher, likely translated the work from French into Armenian prose in 1861 (Dedeyan printing house, Smyrna), with subsequent editions in 1865 and 1876.[21] He noted that it was a free translation by himself. Further Armenian publications, possibly translated from French, appeared in 1895 by Gh. Martirosyan at the Civelegyan publishing house, in 1910 by Rogos Sakayan in Istanbul, and in 1953 by the G. Donigyan printing house in Beirut.

Die kleine Lautenspielerin – Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz

The second story by Christoph von Schmid that garnered significant acclaim and popularity among readers is Die kleine Lautenspielerin (The Little Lute Player).[22]Originally compiled as a play in 1832 and later adapted into a narrative form (Erzählung) in 1833, the story revolves around Countess Teoleninde and her daughter Adelinde. When Teoleninde’s husband, Adelbert, is called to war, the castle is conquered by Grimo von Harteck, who seeks to marry Teoleninde. Fleeing from Grimo’s advances, Teoleninde and Adelinde adopt new identities as Mathilde and Agnes. After enduring various hardships, Adelbert reunites with his wife and daughter, leading to a happy ending.

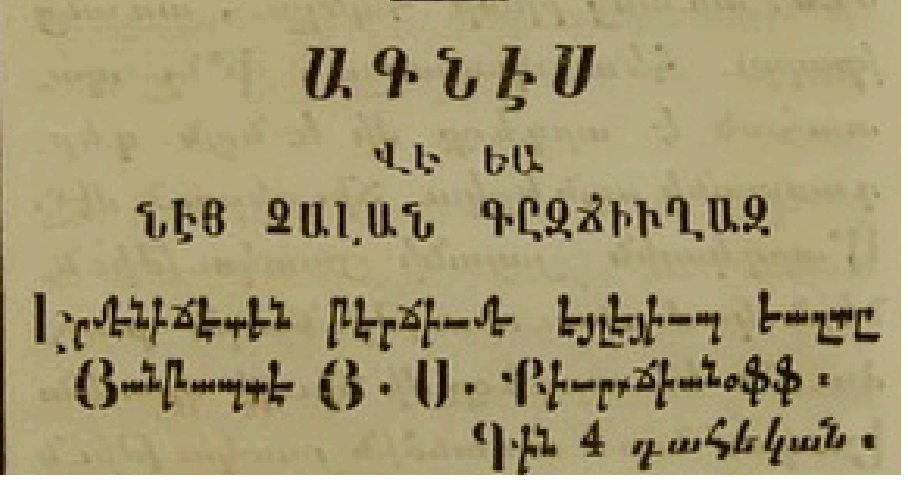

Interestingly, “Die kleine Lautenspielerin” to our knowledge does not appear to have been translated into Karamanlidika or Ottoman Turkish. The Armeno-Turkish version of the story, titled “Aḳnes or the Little Girl Playing the Reed Flute”(Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz) was printed in 1872 by the St. James Armenian Printing House in Jerusalem that was also advertised in the monthly Sion (Սիօն) (see illustration 1) published in Jerusalem on 30 April, 1872, under the heading “new publications”.[23]

Illustration 1: Aḳnes ve ya ney çalan ḳızcüġaz (Aḳnes or the Lute playing little girl) Translated from Armenian [and] written [by] Y. S. Kürkcianoff in Ayntap. The price is 4 piastres.

Translated by Y. S. Kürkcianoff from Ayntap (today’s Gaziantep), the Armeno-Turkish version lacks a preface. However, the cover pages of the first and second editions (1872 and 1885) include a dedication from Kürkcianoff, mentioning Patriarch Yesayi as a patron. He adds a note saying, “it is presented with the fatherly love from its translator to my friend’s offspring Lusia Adur Efendi Nizibliyan” (müterciminden pederane muhabbet ile ihta olunur dosd zadem Lusia Adur efendi Nizibliyane).[24] Apart from stating that he “translated from Armenian,” Kürkcianoff does not mention the intermediary Armenian translator, who must have been Lusi Balasanyan. Balasanyan translated Schmid’s story from a French version into Armenian in 1866 at the Dedeyan printing house in Smyrna, dedicating it to her cousin Levon Kr. Efendi Margosyan.[25]

Although the Armeno-Turkish translation of Aḳnes lacks a preface, the genre and subtitles of both the original and translated versions provide insights into the intended audience. The threefold edition, produced at the St. James Armenian Printing House and patronized by Patriarch Yesayi (sed. 1865-1885), suggests an audience connected to the Armenian Church in Jerusalem. The original was first written as a play and then rewritten as a story, both intended for a female audience, while the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translations are based on the story version. It is plausible that the book was read in schools, such as the first female school (Սրբոց Գայանյանց/ Saint Gayane) established in 1862 in Jerusalem, which operated until 1927.[26] All the versions of Schmid’s The Little Lute-Player —the German original, as well as the French, Armenian, and Armeno-Turkish translations— end with the same quote. The Armeno-Turkish translation even begins and ends with this quote, noting that it is from the “Holy Book” (Aziz Kitab), specifically the fourth of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:12).[27]

Intercultural transmission

Armeno-Turkish translations exhibit characteristics of “tradaptations,” indicating that they are not mere word-for-word translations but rather transpositions and localizations, or subcultures of translation.[28] Unlike original Armeno-Turkish literary works, which often engage in intercommunal debates on religion, society, or modernism, juvenile and devotional literature serves as a platform for presenting role models, particularly pious and chaste women. Furthermore, Armeno-Turkish translators, such as in the case of Aḳnes, frequently replace the names of original religious festivals and terms with Armenian equivalents. This incorporation of Armenian concepts is influenced by the Armenian ‘source’ text available to Y. S. Kürkcianoff, as well as by the intention of the translator and clergy patron to preserve and disseminate Armenian terms familiar to Turkophone Armenian readers. For example, terms such as seġan (altar), S. Haġordutün (Holy Communion), Badaraḳ (the Mass), S. Caşag (Holy Communion), Tsnund (Christmas), cḳnavor (anchorite), uḫdavor (pilgrim), and giragi (Sunday) appear in Armenian and are not translated into Turkish.

A comparison of the texts may provide insights into the source text of the different translations. In the case of Genevieve’s translation versions, variations in the interpretation of names, such as Genevieve’s son, are evident. The use of the name Benon in the Armeno-Turkish translation suggests that it may have been derived from the French translation or that the translator was familiar with both German and French texts. Conversely, the Armenian translation directly translates the German name Schmerzenreich as Ցավակ (Ts’avag), while the Armeno-Turkish translation retains the name Benon from the French translation without translating the meaning of Schmerzenreich into Turkish.

Another notable difference can be observed in a passage describing the shepherds’ hospitality in Aḳnes, indicating that the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translators not only translated but localized the text by incorporating local traditions and familiar dishes. While the original portrays the shepherd’s hospitality as ideal, the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translations emphasise traditional Armenian hospitality (nakhaharts’ and Nahabedagan). The tradaptation goes so far that the German Gemsfleisch, famous in the Alps, is translated into (geyik etinden) ‘pastırma’, a common dish in Turkey and Transcaucasia. The translator adapted the title of the story by changing the lute to a reed and translated ‘Gemsfleisch’ (today Gämsefleisch) through the intermediate French term ‘chamois salé’ and the Armenian translation ‘քարայծի աղած միս’ (salted chamois, wild-goat meat) into the Turkish expression ‘geyik etinden pastırma’. This adaptation was likely intended to present the readership with a familiar process of meat production, even though the meat itself (chamois, which in Turkish would be ‘dağ keçisi’) is not the same as

‘geyik eti’ (venison).[29]

Reception

The Armeno-Turkish translations share a commonality in their number of editions, indicating demand and a certain readership. Yenoveva was edited more than twice between 1855 and 1891, and Aḳnes between 1872 and 1912. The prefaces of these translated works provide valuable insights into their reception. The original intended readership for Yenoveva appears to have been children and mothers, as indicated by the subtitle, “One of the most beautiful and touching stories of antiquity, retold for all good people, especially for mothers and children.” Conversely, the Armeno-Turkish subtitle describes the story as “the beautiful story characterized by laudable moral qualities [and] therefore exemplary for women.”[30] The subtitle of Yenoveva explicitly names women as the audience. In the preface, the printer/publisher underscores this intention, suggesting a degree of warning for female readers:

[…] And although this story is for every class of people, it is especially intended for the women of our nation. Now, as half of them are eager to read, and because those who read our story may find it pleasing and, more importantly, take some lessons from it, the price has been reduced by five ġuruş to make it more affordable. Therefore, compared to its previous price, it will now be sold for ten ġuruş.[31]

The explicit reference to women readers, noting that “now half of them are desiring to read,” can be interpreted from both economic and socio-cultural perspectives. Economically, it suggests a strategy to increase sales by tapping into a growing market of female readers. Socio-culturally, it highlights the evolving interest of women in education and literature, reflecting broader changes in society regarding women’s roles and rights. This statement aligns with the development of feminist ideas and women’s rights debates within the Ottoman Empire. However, the plot itself focuses not on feminist themes but rather on ideals of feminine chastity and virtue.

In contrast to Yenoveva or Genovefa, Aḳnes or The Little Lute-Player features a young girl as one of its two main female protagonists. Schmid’s subtitles indicate a special readership, “children and friends of children,” but the translations, especially the Armeno-Turkish one, likely also targeted older female readers. This is suggested by the prominent role of Matilda (Teoleninda), Aḳnes’ (Adelinde’s) mother. Matilda is a dominant character whose emotional condition is frequently highlighted by the narrator, while Aḳnes is depicted as a brave, obedient girl. Matilda’s resistance to an evil tyrant and her efforts to live in honour likely broadened the story’s appeal, attracting a wider readership than just children and their friends. In addition to promoting Christian virtues and good attitudes, publishers aimed to sell popular stories translated from Western languages into Armenian and Armeno-Turkish. The continued printing of the Armenian version until 1953 (Beirut) suggests the story maintained its popularity among Armenian readers for a long period.

Conclusions

These translations are not mere replicas of their originals but are nuanced “tradaptations” that incorporate local traditions and linguistic elements, highlighting the rich interplay between different cultural and religious communities within the Ottoman Empire.

The popularity of Genovefa and Die kleine Lautenspielerin across various scripts and languages indicates the widespread appeal and cultural resonance of these stories. The involvement of Armenian printing houses and the adaptation of these works into Armenian and Armeno-Turkish versions suggests a vibrant literary culture that transcended linguistic and religious boundaries. The targeted readership of these translations, particularly women and children, reflects broader socio-cultural trends, including the growing interest in education and the changing roles of women in society. The adaptation strategies employed by translators like Y. S. Kürkcianoff, who localised the texts by incorporating familiar Armenian terms and traditions, illustrate the translators’ efforts to make these stories accessible and relevant to their audiences. Examining the reception and impact of these translations makes it evident that Armeno-Turkish literature played a significant role in shaping the literary and cultural milieu of the late Ottoman period. The continued popularity and multiple editions of these works attest to their enduring influence and the important role of translation in cultural exchange and preservation.

[1] Sebouh D. Aslanian, ““Prepared in the language of the Hagarites:” Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, 25 (2016): 54-86.

[2] See Murat Cankara, “Armeno-Turkish Writing and the Question of Hybridity,” in An Armenian Mediterranean: Words and Worlds in Motion, ed. Kathryn Babayan and Michael Pifer (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 173-191; Aram Ghoogasian, “The problem with hybridity: a critique of Armeno-Turkish Studies,” Middle Eastern Literatures, 25:1 (2022): 39-56.

[3] Laurent Mignon, “Lost in Transliteration: a few remarks on the Armeno-Turkish novel and Turkish Literary Historiography,” in Between Religion and Language, Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, ed. Evangelia Balta and Mehmet Ölmez (Istanbul: Eren, 2011), 111-23, here 123.

[4] Johann Strauss, “Is Karamanli Literature part of a “Christian-Turkish (Turco-Christian) Literature?,” in Cries and Whispers in Karamanlidika Books, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Karamanlidika Studies (Nicosia, 11-13 September 2008), ed. Evangelia Balta and Matthias Kappler, (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010), 155-200, 155.

[5] Laurent Mignon, Uncoupling Language and Religion. An Exploration into the Margins of Turkish Literature (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2021), 69-70.

[6] Armin Hetzer, Dačkerēn-Texte: Eine Chrestomathie aus Armenierdrucken des 19. Jahrhunderts in türkischer Sprache (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1987), 58.

[7] Hans Pörnbacher, ed., Christoph von Schmid. Genovefa. Eine der schönsten und rührendsten Geschichten des Alterthums neuerzählt für alle guten Menschen (Weißenhorn: Anton H. Konrad Verlag, 2018), see especially the epilogue by Pörnbacher, 173-203.

[8] See Günil Özlem Ayaydın Cebe, “19. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Toplumu ve Basılı Türkçe Edebiyat- Etkileşimler, Değişimler, Çeşitlilik” (PhD diss., Ankara: Bilkent University, 2009), 249.

[9] The Karamanlidika version of Yenovefa was also subject to a Phd thesis conducted by Perihan Kaya, “Karamanlı Türkçesi üzerine dil çalışması: “Yenovefa hikayesi” (çeviri yazı-dil incelemesi-dizin),” (PhD diss., Ankara: Hacettepe University, 2016).

[10] Teotig. Baskı ve Harf. Ermeni Matbaacılık Tarihi, [Çeviri: Sirvart Malhasyan, Arlet İncidüzen] (Istanbul, Birzamanlar Yayıncılık, 2012), 112-14.

[11] It is possible that the Armeno-Turkish version was translated from the Greek/Karamanlidika version of 1854 that in its turn was translated from the French version. For Hovsep Kafavyan and his printing house, see Teotig. Baskı ve Harf, 118-21.

[12] Yenoveva Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnüma Olmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise, Asitane [Istanbul]: Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan tabḫanesinde,1868, 3. For a digitized version available at the National Library of Armenia see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/eenoveva_1868.pdf.

[13] See Ayaydın Cebe, “19. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Toplumu ve Basılı Türkçe Edebiyat,” 249; cf. Kaya, “Karamanlı Türkçesi üzerine dil çalışması,” 34-36.

[14] There is a digitized version available at the İBB Atatürk Kitaplığı under the title Tercüme-i hikaye-i Jöneviyo / Cristoph von Schmid, mütercimi Memduh Paşa.

[15] Günil Özlem Ayaydın Cebe, “To Translate or Not to Translate? 19th Century Ottoman Communities and Fiction,” Die Welt des Islams 56 (2016): 187-222, here 202 referring to Johann Strauss, “Who read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?”, Middle Eastern Literatures, 6:1 (2003): 39-76, 75 and suggesting that “The mistake probably results from a similarity of name.” For Memduh Paşa see Zekeriya Kurşun, “Mehmed Memduh Paşa,” in TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi 28 (2003), 495-97 (https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mehmed-memduh-pasa).

[16] Although we were not able to compare the Armeno-Turkish and the Ottoman version as a whole yet, comparisons of certain parts let us conclude that the Armeno-Turkish version is written in a much clearer “Turkish”, not containing as much complicate structures or izafets as the Ottoman Turkish version of Memduh Paşa.

[17] Strauss, “Who read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?,” 63.

[18] The original Armenian title of the translated story was “Պատմութիւն Գենովափէի, դքսուհիոյն Բրիտանիոյ” The digitised version of the work is available at the National Library of Armenia https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1801-1850/patmutyun_genovapei1849.pdf.

[19] Ardashes Kardashian, Matenagitutʻiwn Hayataṛ Ōtar Lezwov Tpagir Girkʻeru) [Bibliography of Armenian print foreign books.] (Paris: Ṛubēn Sewak” Mshakutʻayin Himnarki, 1987), 150; cf. Sabri Koz, “Bîdârî”, Dünden Bugüne İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, vol. 2․ (Istanbul: Ana Basım AŞ, 1994): 227-28. For Mihran Arabacyan (or Mihran Bidar Arabacyan) see Murat Canka, “İmparatorluk ve Roman: Ermeni harfli Türkçe romanları Osmanlı/Türk edebiyat tarihyazımında konumlandırmak” (PhD diss., Ankara: İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent Üniversitesi, 2011), 242-46; numerous works of Arabacyan are digitized and available at the National Library of Armenia.

[20] Dikran- Haroutiun Dedeyan’s printing house, established in Smyrna, played a big role in expansion of translated secular literature in Armenian starting from 1853 until 1884 publishing 63 literary translations. See more on the Dedeyan publishing house and translations and collaborations between publishing house and translators, Jennifer Manoukian, “Literary translation and the expansion of the Ottoman Armenian Reading Public, 1853-1884,” Book History 25, 1 (2022): 128-71; Jennifer Manoukian, “The Dedeyan Publishing House of Smyrna, 1853-1892,” https://www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-aydinizmir/literature/printing.html.

[21] The third publication before 1876 is unknown and we had no access to it so far. See Manoukian, “The Dedeyan Publishing House of Smyrna, 1853-1892.” For a digitized version of the Armenian translation available at the National Library of Armenia see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/agnes1866.pdf; an Armeno-Turkish version is available as well, see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/agnes_ve1872.pdf.

[22] Die kleine Lautenspielerin. Eine Erzählung für Kinder und Kinderfreunde nach dem Schauspiele gleichen Namens von Christoph von Schmid, Verfasser der Ostereier. Neue illustrierte Originalauflage. Mit Stahlstich und feinen Holzschnittbildern. Regensburg: Verlagsanstalt vorm. G. J. Manz, n. d..

[23] See Sion 4 (1872, April 30), 96. We know of at least three Armeno-Turkish prints. After the first print of 1872 followed a second print in 1885, and a third print in 1912. The Armeno-Turkish translation of Aḳnes was studied recently by Berna Sert, “19. yüzyıla ait Ermeni harfli Türkçe Agnes veya ney çalan Kızcığaz hikayesi (çeviriyazı, aktarma, inceleme, gramatikal dizin, tıpkıbasım),” (MA thesis, Ordu University, 2021).

[24] See Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz, Ermeniceden tercime eyledi Antebli Y. S. Kürkcianoff (Ḳuds Şerif [Jerusalem]: Mar Yaḳub manastırın basmahanesinde, 1872), 3. So far, we have no further information about the named person to whom the print is dedicated but we can assume that she was one of the sponsors of the St. James printing house.

[25] Manoukian, “Literary translation and the expansion of the Ottoman Armenian Reading Public, 1853-1884,” fn. 136.

[26] Maghakʻia Ormanyan, Haygagan Erusaghem [Armenian Jerusalem], (Jerusalem: St. Jakob, 1931), 86-87.

[27] “Honor your father and your mother, so that you will have a long life and you will grow with prosperity on the Earth. Holy Book”.

[28] For translation as a lingua franca and a “mode of worlding the local” see Marilyn Booth, “Introduction: Translation as Lateral Cosmopolitanism in the Ottoman Universe,” in Marilyn Booth (ed.), Migrating Texts. Circulating Translations around the Ottoman Mediterranean (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 1-54, here 42-44.

[29] For the French version we used Oeuvres du Chanoine Christophe Schmid. I. Agnès ou la petite joueuse de luth. Leipsic: Théodore Thomas, 1848. This print is available at https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/benjamin/content/titleinfo/12069372 (digitized by Universitätsbibliothek J.C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main).

[30] Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnümaOlmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise.

[31] Yenoveva Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnüma Olmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise, (Asitane[Istanbul]: Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan tabḫanesinde, 1868), 3-4․