Emre Görkem Onur: “Writing a Monologue in Armeno-Turkish: The Case of Hagop Ayvaz”

Tobias Sick: “Reading Persian Advice Literature in Armeno-Turkish: Some Notes on the History of the ‘Pearl-Ornated Pendnāme’”

Emre Görkem Onur: “Writing a Monologue in Armeno-Turkish: The Case of Hagop Ayvaz”

Tobias Sick: “Reading Persian Advice Literature in Armeno-Turkish: Some Notes on the History of the ‘Pearl-Ornated Pendnāme’”

Hülya Çelik (Ruhr University Bochum) and Ani Sargsyan (University of Hamburg)

Introduction

Detailed comparative studies of the multidimensional nature of translations, particularly those in Armeno-Turkish, provide fresh perspectives on the diverse Ottoman literary landscape of the second half of the nineteenth century. This article draws on concepts such as “between two stools,” “Christian Turkish literature,” and “Turkish Kulturchristentum” (proposed by Johann Strauss and Laurent Mignon) to explore the transregional and inner-Ottoman translation trajectories of Armeno-Turkish literature. By examining two selected translations of Christoph von Schmid’s (1768-1854) works, this study explores the ecologies of translation, highlighting the significance of translation in the mobility and appropriation of ideas and texts.

A transimperial approach to translation and multilingualism broadens the scope beyond the dominant religious tradition of Islam and its “three languages” (elsine-i s̱elās̱e), as commonly emphasised in Ottoman studies. This approach enables a deeper exploration of the multireligious context within the Ottoman Empire and beyond, shedding light on common patterns regarding the significance of sacred languages across various religious communities. It examines the relationship between these sacred languages and vernaculars, the intricacies of translating between them, and the challenges of rendering religious texts into vernacular or foreign languages, printed forms, and different scripts.

Being “in-between” or “fallen between two stools,” Armeno-Turkish novels and other genres—translations as well as original works—have never found a place in Armenian or Turkish literary canons. However, the extensive presence of Armeno-Turkish printed material suggests this phenomenon was not extraordinary “exotic” for its time. Instead, it reflects the commonplace existence of cross-cultural contact zones in late Ottoman cities such as Istanbul, Smyrna/Izmir, Aleppo, and Jerusalem.[1] This literature demonstrates the complex interplay of languages and broader cultural interactions within the late Ottoman period.[2] Building on Laurent Mignon’s insights, this paper seeks to uncover a shared cultural heritage, echoing Hrant Dink’s concept of ‘the common memory’ of the Turkish and Armenian people.[3] By considering the concepts of Christian Turkish (Turco-Christian) literature[4] and “Turkish Kulturchristentum”,[5] and viewing Armeno-Turkish not merely as a dialect but as a functional style,[6] we highlight its role in the broader landscape of Ottoman multilingualism, examining its impact alongside Ottoman Turkish and Western Armenian literary works.

The flourishing of Armeno-Turkish literary production in the nineteenth century was significantly supported by Armenian printing houses in key Ottoman cities and the Mkhitarist printing houses in Europe (Vienna, San Lazzaro, Trieste). This network facilitated the dissemination of European literary works, including those by Christoph von Schmid, a prominent figure in eighteenth-century German literature known for his juvenile and devotional narratives (fromme Literatur). Schmid’s works resonated deeply across various Ottoman communities, emphasizing the broad appeal and cultural impact of Armeno-Turkish translations, which often preceded their Ottoman Turkish and Armenian versions.

This paper shows how these translations influenced Armeno-Turkish language and mixed cultural identities, revealing intricate translation practices and broader cultural implications. By analysing Christoph von Schmid’s works in translation, this paper aims to enhance our understanding of the complex web of translation, adaptation, and cultural transmission within the Ottoman Empire.

Genovefa – Genevieve – Yenoveva

The first and perhaps most cherished story examined in this context, which captivated both European readers and resonated within the Ottoman Empire, particularly among the Christian population, is Genovefa. This tale, based on the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, was rewritten in German by Christoph von Schmid and first published in 1810.[7]

The narrative had a widespread popularity throughout the Ottoman realm.[8] The story was evidently so well-loved that it was adapted into all three scripts—Greek, Armenian, and Arabic—used by Turkish-speaking and reading Ottomans of the time.[9]

The Armeno-Turkish translation of Yenoveva is attributed to an unknown translator, first published in 1855 and again in 1868 by the printing house of Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan in Istanbul.[10] Subsequent editions followed in 1890 and 1891, the latter printed by the Kavafyan printing house.[11] The preface (dibace) of the second edition, likely authored by Kürkcyan himself, hints at dissatisfaction regarding the delayed release, which took 13 years to produce 500 copies. Kürkcyan even adopts a tone of sarcasm, jesting that this second edition would probably endure until the end of his life, as expressed in the following passage:

…As it is the knowledge of the experts of reading [and] this story of ours had been printed once before and sold out …, Given that some enthusiasts have expressed a desire to read it, it has been deemed appropriate and fitting to print it again, this time without hesitation, in a neat and clean edition. However, we regret to say that while the first printing was in 1855, the second could only be done in 1868. That is, in exactly thirteen years, our little book could only be circulated with great difficulty in five hundred copies. And this time, it is beyond doubt that it will take just as long, meaning it can send us off to the other world. There is no doubt that the third printing will either be done by those who come after us, or we might do it upon our return […].[12]

The Karamanlidika version first appeared in 1854, translated by Evangelinos Misailidis and printed by the Anatoli publishing house, with a second edition printed between 1860 and 1870.[13] An Ottoman Turkish translation surfaced in 1868, attributed to Tatyos Dividjyan’s printing house and translated by Mehmed Memduh Paşa, the Minister of the Interior.[14] Some secondary sources mistakenly claimed that the original was written by Lamartine; however, this is incorrect.[15] Memduh Paşa’s translation was published only once, likely due to its “strange” and complicated Ottoman style of language.[16] Additionally, the story of Genevieve was also known to the Arab-reading public, likely translated from a French edition.[17]

The Armenian-speaking population also had access to this popular story. In 1849 (and subsequently in 1858, 1872, and 1900), the Mkhitarist Father of Venice, Vrtanes Buduryan, translated it into Armenian as History of Genovape, Duchess of Britain.[18] A rhymed Armenian version was translated into Armeno-Turkish by Mihran Arabacyan (d. 1898) in 1886 under his pen name Bidar, published by the Kavafyan printing house and entitled Ḳenovape nam Afıfe Ḳadının Hikyayei Ġaribesi, İngiltera Düşesalerınden.[19] Dikran-Haroutiun Dedeyan (1832-1868),[20] a prolific translator and publisher, likely translated the work from French into Armenian prose in 1861 (Dedeyan printing house, Smyrna), with subsequent editions in 1865 and 1876.[21] He noted that it was a free translation by himself. Further Armenian publications, possibly translated from French, appeared in 1895 by Gh. Martirosyan at the Civelegyan publishing house, in 1910 by Rogos Sakayan in Istanbul, and in 1953 by the G. Donigyan printing house in Beirut.

Die kleine Lautenspielerin – Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz

The second story by Christoph von Schmid that garnered significant acclaim and popularity among readers is Die kleine Lautenspielerin (The Little Lute Player).[22]Originally compiled as a play in 1832 and later adapted into a narrative form (Erzählung) in 1833, the story revolves around Countess Teoleninde and her daughter Adelinde. When Teoleninde’s husband, Adelbert, is called to war, the castle is conquered by Grimo von Harteck, who seeks to marry Teoleninde. Fleeing from Grimo’s advances, Teoleninde and Adelinde adopt new identities as Mathilde and Agnes. After enduring various hardships, Adelbert reunites with his wife and daughter, leading to a happy ending.

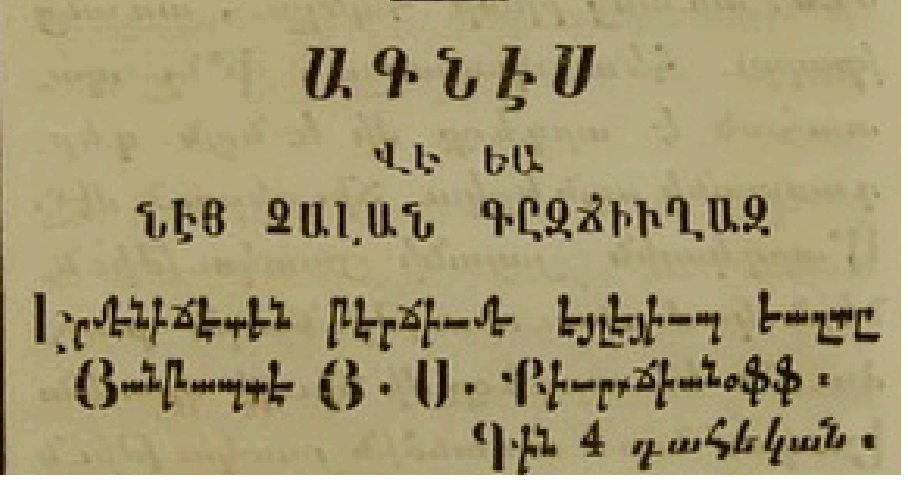

Interestingly, “Die kleine Lautenspielerin” to our knowledge does not appear to have been translated into Karamanlidika or Ottoman Turkish. The Armeno-Turkish version of the story, titled “Aḳnes or the Little Girl Playing the Reed Flute”(Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz) was printed in 1872 by the St. James Armenian Printing House in Jerusalem that was also advertised in the monthly Sion (Սիօն) (see illustration 1) published in Jerusalem on 30 April, 1872, under the heading “new publications”.[23]

Illustration 1: Aḳnes ve ya ney çalan ḳızcüġaz (Aḳnes or the Lute playing little girl) Translated from Armenian [and] written [by] Y. S. Kürkcianoff in Ayntap. The price is 4 piastres.

Translated by Y. S. Kürkcianoff from Ayntap (today’s Gaziantep), the Armeno-Turkish version lacks a preface. However, the cover pages of the first and second editions (1872 and 1885) include a dedication from Kürkcianoff, mentioning Patriarch Yesayi as a patron. He adds a note saying, “it is presented with the fatherly love from its translator to my friend’s offspring Lusia Adur Efendi Nizibliyan” (müterciminden pederane muhabbet ile ihta olunur dosd zadem Lusia Adur efendi Nizibliyane).[24] Apart from stating that he “translated from Armenian,” Kürkcianoff does not mention the intermediary Armenian translator, who must have been Lusi Balasanyan. Balasanyan translated Schmid’s story from a French version into Armenian in 1866 at the Dedeyan printing house in Smyrna, dedicating it to her cousin Levon Kr. Efendi Margosyan.[25]

Although the Armeno-Turkish translation of Aḳnes lacks a preface, the genre and subtitles of both the original and translated versions provide insights into the intended audience. The threefold edition, produced at the St. James Armenian Printing House and patronized by Patriarch Yesayi (sed. 1865-1885), suggests an audience connected to the Armenian Church in Jerusalem. The original was first written as a play and then rewritten as a story, both intended for a female audience, while the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translations are based on the story version. It is plausible that the book was read in schools, such as the first female school (Սրբոց Գայանյանց/ Saint Gayane) established in 1862 in Jerusalem, which operated until 1927.[26] All the versions of Schmid’s The Little Lute-Player —the German original, as well as the French, Armenian, and Armeno-Turkish translations— end with the same quote. The Armeno-Turkish translation even begins and ends with this quote, noting that it is from the “Holy Book” (Aziz Kitab), specifically the fourth of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:12).[27]

Intercultural transmission

Armeno-Turkish translations exhibit characteristics of “tradaptations,” indicating that they are not mere word-for-word translations but rather transpositions and localizations, or subcultures of translation.[28] Unlike original Armeno-Turkish literary works, which often engage in intercommunal debates on religion, society, or modernism, juvenile and devotional literature serves as a platform for presenting role models, particularly pious and chaste women. Furthermore, Armeno-Turkish translators, such as in the case of Aḳnes, frequently replace the names of original religious festivals and terms with Armenian equivalents. This incorporation of Armenian concepts is influenced by the Armenian ‘source’ text available to Y. S. Kürkcianoff, as well as by the intention of the translator and clergy patron to preserve and disseminate Armenian terms familiar to Turkophone Armenian readers. For example, terms such as seġan (altar), S. Haġordutün (Holy Communion), Badaraḳ (the Mass), S. Caşag (Holy Communion), Tsnund (Christmas), cḳnavor (anchorite), uḫdavor (pilgrim), and giragi (Sunday) appear in Armenian and are not translated into Turkish.

A comparison of the texts may provide insights into the source text of the different translations. In the case of Genevieve’s translation versions, variations in the interpretation of names, such as Genevieve’s son, are evident. The use of the name Benon in the Armeno-Turkish translation suggests that it may have been derived from the French translation or that the translator was familiar with both German and French texts. Conversely, the Armenian translation directly translates the German name Schmerzenreich as Ցավակ (Ts’avag), while the Armeno-Turkish translation retains the name Benon from the French translation without translating the meaning of Schmerzenreich into Turkish.

Another notable difference can be observed in a passage describing the shepherds’ hospitality in Aḳnes, indicating that the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translators not only translated but localized the text by incorporating local traditions and familiar dishes. While the original portrays the shepherd’s hospitality as ideal, the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish translations emphasise traditional Armenian hospitality (nakhaharts’ and Nahabedagan). The tradaptation goes so far that the German Gemsfleisch, famous in the Alps, is translated into (geyik etinden) ‘pastırma’, a common dish in Turkey and Transcaucasia. The translator adapted the title of the story by changing the lute to a reed and translated ‘Gemsfleisch’ (today Gämsefleisch) through the intermediate French term ‘chamois salé’ and the Armenian translation ‘քարայծի աղած միս’ (salted chamois, wild-goat meat) into the Turkish expression ‘geyik etinden pastırma’. This adaptation was likely intended to present the readership with a familiar process of meat production, even though the meat itself (chamois, which in Turkish would be ‘dağ keçisi’) is not the same as

‘geyik eti’ (venison).[29]

Reception

The Armeno-Turkish translations share a commonality in their number of editions, indicating demand and a certain readership. Yenoveva was edited more than twice between 1855 and 1891, and Aḳnes between 1872 and 1912. The prefaces of these translated works provide valuable insights into their reception. The original intended readership for Yenoveva appears to have been children and mothers, as indicated by the subtitle, “One of the most beautiful and touching stories of antiquity, retold for all good people, especially for mothers and children.” Conversely, the Armeno-Turkish subtitle describes the story as “the beautiful story characterized by laudable moral qualities [and] therefore exemplary for women.”[30] The subtitle of Yenoveva explicitly names women as the audience. In the preface, the printer/publisher underscores this intention, suggesting a degree of warning for female readers:

[…] And although this story is for every class of people, it is especially intended for the women of our nation. Now, as half of them are eager to read, and because those who read our story may find it pleasing and, more importantly, take some lessons from it, the price has been reduced by five ġuruş to make it more affordable. Therefore, compared to its previous price, it will now be sold for ten ġuruş.[31]

The explicit reference to women readers, noting that “now half of them are desiring to read,” can be interpreted from both economic and socio-cultural perspectives. Economically, it suggests a strategy to increase sales by tapping into a growing market of female readers. Socio-culturally, it highlights the evolving interest of women in education and literature, reflecting broader changes in society regarding women’s roles and rights. This statement aligns with the development of feminist ideas and women’s rights debates within the Ottoman Empire. However, the plot itself focuses not on feminist themes but rather on ideals of feminine chastity and virtue.

In contrast to Yenoveva or Genovefa, Aḳnes or The Little Lute-Player features a young girl as one of its two main female protagonists. Schmid’s subtitles indicate a special readership, “children and friends of children,” but the translations, especially the Armeno-Turkish one, likely also targeted older female readers. This is suggested by the prominent role of Matilda (Teoleninda), Aḳnes’ (Adelinde’s) mother. Matilda is a dominant character whose emotional condition is frequently highlighted by the narrator, while Aḳnes is depicted as a brave, obedient girl. Matilda’s resistance to an evil tyrant and her efforts to live in honour likely broadened the story’s appeal, attracting a wider readership than just children and their friends. In addition to promoting Christian virtues and good attitudes, publishers aimed to sell popular stories translated from Western languages into Armenian and Armeno-Turkish. The continued printing of the Armenian version until 1953 (Beirut) suggests the story maintained its popularity among Armenian readers for a long period.

Conclusions

These translations are not mere replicas of their originals but are nuanced “tradaptations” that incorporate local traditions and linguistic elements, highlighting the rich interplay between different cultural and religious communities within the Ottoman Empire.

The popularity of Genovefa and Die kleine Lautenspielerin across various scripts and languages indicates the widespread appeal and cultural resonance of these stories. The involvement of Armenian printing houses and the adaptation of these works into Armenian and Armeno-Turkish versions suggests a vibrant literary culture that transcended linguistic and religious boundaries. The targeted readership of these translations, particularly women and children, reflects broader socio-cultural trends, including the growing interest in education and the changing roles of women in society. The adaptation strategies employed by translators like Y. S. Kürkcianoff, who localised the texts by incorporating familiar Armenian terms and traditions, illustrate the translators’ efforts to make these stories accessible and relevant to their audiences. Examining the reception and impact of these translations makes it evident that Armeno-Turkish literature played a significant role in shaping the literary and cultural milieu of the late Ottoman period. The continued popularity and multiple editions of these works attest to their enduring influence and the important role of translation in cultural exchange and preservation.

[1] Sebouh D. Aslanian, ““Prepared in the language of the Hagarites:” Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, 25 (2016): 54-86.

[2] See Murat Cankara, “Armeno-Turkish Writing and the Question of Hybridity,” in An Armenian Mediterranean: Words and Worlds in Motion, ed. Kathryn Babayan and Michael Pifer (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 173-191; Aram Ghoogasian, “The problem with hybridity: a critique of Armeno-Turkish Studies,” Middle Eastern Literatures, 25:1 (2022): 39-56.

[3] Laurent Mignon, “Lost in Transliteration: a few remarks on the Armeno-Turkish novel and Turkish Literary Historiography,” in Between Religion and Language, Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, ed. Evangelia Balta and Mehmet Ölmez (Istanbul: Eren, 2011), 111-23, here 123.

[4] Johann Strauss, “Is Karamanli Literature part of a “Christian-Turkish (Turco-Christian) Literature?,” in Cries and Whispers in Karamanlidika Books, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Karamanlidika Studies (Nicosia, 11-13 September 2008), ed. Evangelia Balta and Matthias Kappler, (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010), 155-200, 155.

[5] Laurent Mignon, Uncoupling Language and Religion. An Exploration into the Margins of Turkish Literature (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2021), 69-70.

[6] Armin Hetzer, Dačkerēn-Texte: Eine Chrestomathie aus Armenierdrucken des 19. Jahrhunderts in türkischer Sprache (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1987), 58.

[7] Hans Pörnbacher, ed., Christoph von Schmid. Genovefa. Eine der schönsten und rührendsten Geschichten des Alterthums neuerzählt für alle guten Menschen (Weißenhorn: Anton H. Konrad Verlag, 2018), see especially the epilogue by Pörnbacher, 173-203.

[8] See Günil Özlem Ayaydın Cebe, “19. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Toplumu ve Basılı Türkçe Edebiyat- Etkileşimler, Değişimler, Çeşitlilik” (PhD diss., Ankara: Bilkent University, 2009), 249.

[9] The Karamanlidika version of Yenovefa was also subject to a Phd thesis conducted by Perihan Kaya, “Karamanlı Türkçesi üzerine dil çalışması: “Yenovefa hikayesi” (çeviri yazı-dil incelemesi-dizin),” (PhD diss., Ankara: Hacettepe University, 2016).

[10] Teotig. Baskı ve Harf. Ermeni Matbaacılık Tarihi, [Çeviri: Sirvart Malhasyan, Arlet İncidüzen] (Istanbul, Birzamanlar Yayıncılık, 2012), 112-14.

[11] It is possible that the Armeno-Turkish version was translated from the Greek/Karamanlidika version of 1854 that in its turn was translated from the French version. For Hovsep Kafavyan and his printing house, see Teotig. Baskı ve Harf, 118-21.

[12] Yenoveva Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnüma Olmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise, Asitane [Istanbul]: Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan tabḫanesinde,1868, 3. For a digitized version available at the National Library of Armenia see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/eenoveva_1868.pdf.

[13] See Ayaydın Cebe, “19. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Toplumu ve Basılı Türkçe Edebiyat,” 249; cf. Kaya, “Karamanlı Türkçesi üzerine dil çalışması,” 34-36.

[14] There is a digitized version available at the İBB Atatürk Kitaplığı under the title Tercüme-i hikaye-i Jöneviyo / Cristoph von Schmid, mütercimi Memduh Paşa.

[15] Günil Özlem Ayaydın Cebe, “To Translate or Not to Translate? 19th Century Ottoman Communities and Fiction,” Die Welt des Islams 56 (2016): 187-222, here 202 referring to Johann Strauss, “Who read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?”, Middle Eastern Literatures, 6:1 (2003): 39-76, 75 and suggesting that “The mistake probably results from a similarity of name.” For Memduh Paşa see Zekeriya Kurşun, “Mehmed Memduh Paşa,” in TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi 28 (2003), 495-97 (https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mehmed-memduh-pasa).

[16] Although we were not able to compare the Armeno-Turkish and the Ottoman version as a whole yet, comparisons of certain parts let us conclude that the Armeno-Turkish version is written in a much clearer “Turkish”, not containing as much complicate structures or izafets as the Ottoman Turkish version of Memduh Paşa.

[17] Strauss, “Who read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?,” 63.

[18] The original Armenian title of the translated story was “Պատմութիւն Գենովափէի, դքսուհիոյն Բրիտանիոյ” The digitised version of the work is available at the National Library of Armenia https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1801-1850/patmutyun_genovapei1849.pdf.

[19] Ardashes Kardashian, Matenagitutʻiwn Hayataṛ Ōtar Lezwov Tpagir Girkʻeru) [Bibliography of Armenian print foreign books.] (Paris: Ṛubēn Sewak” Mshakutʻayin Himnarki, 1987), 150; cf. Sabri Koz, “Bîdârî”, Dünden Bugüne İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, vol. 2․ (Istanbul: Ana Basım AŞ, 1994): 227-28. For Mihran Arabacyan (or Mihran Bidar Arabacyan) see Murat Canka, “İmparatorluk ve Roman: Ermeni harfli Türkçe romanları Osmanlı/Türk edebiyat tarihyazımında konumlandırmak” (PhD diss., Ankara: İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent Üniversitesi, 2011), 242-46; numerous works of Arabacyan are digitized and available at the National Library of Armenia.

[20] Dikran- Haroutiun Dedeyan’s printing house, established in Smyrna, played a big role in expansion of translated secular literature in Armenian starting from 1853 until 1884 publishing 63 literary translations. See more on the Dedeyan publishing house and translations and collaborations between publishing house and translators, Jennifer Manoukian, “Literary translation and the expansion of the Ottoman Armenian Reading Public, 1853-1884,” Book History 25, 1 (2022): 128-71; Jennifer Manoukian, “The Dedeyan Publishing House of Smyrna, 1853-1892,” https://www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-aydinizmir/literature/printing.html.

[21] The third publication before 1876 is unknown and we had no access to it so far. See Manoukian, “The Dedeyan Publishing House of Smyrna, 1853-1892.” For a digitized version of the Armenian translation available at the National Library of Armenia see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/agnes1866.pdf; an Armeno-Turkish version is available as well, see https://haygirk.nla.am/upload/1512-1940/1851-1900/agnes_ve1872.pdf.

[22] Die kleine Lautenspielerin. Eine Erzählung für Kinder und Kinderfreunde nach dem Schauspiele gleichen Namens von Christoph von Schmid, Verfasser der Ostereier. Neue illustrierte Originalauflage. Mit Stahlstich und feinen Holzschnittbildern. Regensburg: Verlagsanstalt vorm. G. J. Manz, n. d..

[23] See Sion 4 (1872, April 30), 96. We know of at least three Armeno-Turkish prints. After the first print of 1872 followed a second print in 1885, and a third print in 1912. The Armeno-Turkish translation of Aḳnes was studied recently by Berna Sert, “19. yüzyıla ait Ermeni harfli Türkçe Agnes veya ney çalan Kızcığaz hikayesi (çeviriyazı, aktarma, inceleme, gramatikal dizin, tıpkıbasım),” (MA thesis, Ordu University, 2021).

[24] See Aḳnes ve yaḫod ney çalan ḳızcıġaz, Ermeniceden tercime eyledi Antebli Y. S. Kürkcianoff (Ḳuds Şerif [Jerusalem]: Mar Yaḳub manastırın basmahanesinde, 1872), 3. So far, we have no further information about the named person to whom the print is dedicated but we can assume that she was one of the sponsors of the St. James printing house.

[25] Manoukian, “Literary translation and the expansion of the Ottoman Armenian Reading Public, 1853-1884,” fn. 136.

[26] Maghakʻia Ormanyan, Haygagan Erusaghem [Armenian Jerusalem], (Jerusalem: St. Jakob, 1931), 86-87.

[27] “Honor your father and your mother, so that you will have a long life and you will grow with prosperity on the Earth. Holy Book”.

[28] For translation as a lingua franca and a “mode of worlding the local” see Marilyn Booth, “Introduction: Translation as Lateral Cosmopolitanism in the Ottoman Universe,” in Marilyn Booth (ed.), Migrating Texts. Circulating Translations around the Ottoman Mediterranean (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 1-54, here 42-44.

[29] For the French version we used Oeuvres du Chanoine Christophe Schmid. I. Agnès ou la petite joueuse de luth. Leipsic: Théodore Thomas, 1848. This print is available at https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/benjamin/content/titleinfo/12069372 (digitized by Universitätsbibliothek J.C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main).

[30] Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnümaOlmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise.

[31] Yenoveva Yani Ahlaḳı Hamideyle Mevsuf Lihaza Nisa Taifesine İbretnüma Olmaya Maḫsus Hikyayeyi Nefise, (Asitane[Istanbul]: Ṙupen H. Kürkcyan tabḫanesinde, 1868), 3-4․

Naira Poghosyan (Yerevan State University)

Introduction

The convergence of diverse nations, religions, and languages within the borders of an empire often fosters the emergence of unique, hybrid cultures. Armeno-Turkish, a form of Turkish written using the Armenian script [Western Armenian: Armenian letter Turkish:[1] – Hayata ṛ T’r’keren], exemplifies this cultural synthesis within the Ottoman Empire.[2] The Armeno-Turkish heritage spans a wide range of genres and subjects, including religious text translations, novels, plays, dictionaries, textbooks, periodicals, newspapers, diaries, memoirs, and private letters.[3]

This article examines a memoir written in Armeno-Turkish in the Soviet Armenia by Penon Vasilyan, a survivor of the Armenian genocide from the town of Dörtyol (Western Armenian: Чорк Marzpan – Chʻorkʻ Marzpan) in the Hatay region of modern Turkey. By analysing Penon Vasilyan’s memoirs as a case study this article will first focus on the patterns of the utilisation of Armeno-Turkish as a ‘product’ imported to a new geography by the Armenian survivors. Secondly, it aims to elucidate the main themes addressed by the narrator and to explore the distinctive ways in which Armeno-Turkish was employed in the everyday lives of Ottoman Armenians.

This study contributes to the limited but growing body of research on post-1915 Armeno-Turkish literature. While most existing research focuses on earlier works, this article highlights the significance of Vasilyan’s memoir, drawing scholarly attention to an understudied period that holds significant potential for further research.

Writing Armenian, Reading Turkish: “Dissonant” heritage of the Ottoman Armenians

Numerous interrelated cultural, social, and political factors favored the flourishing of Armen-Turkish throughout the 19th century. The widespread production of printed works in Armeno-Turkish during this period is a testament to its significance. However, during the early 20th century, there was a noticeable decline in the use of Armeno-Turkish, a trend that accelerated significantly after the events of 1915. Despite this decline, Armeno-Turkish continued to be used by Armenian survivors around the world, albeit less commonly. For several decades, Armeno-Turkish persisted in various communities where Armenians had settled, helping to preserve their cultural and linguistic heritage[4] despite the increasing prominence of Armenian. This continued, albeit reduced usage, highlights the resilience of the Armenian people in maintaining their linguistic traditions amid changing circumstances. Over time, the intangible heritage of Armeno-Turkish, which Armenians carried to their new home countries, became “dissonant.” This dissonance arises from the contrast between the continued existence of Armenian cultural elements abroad and the near-total elimination of Armenian presence in Turkey. The concept of “dissonant heritage,” as articulated by Tunbridge and Ashworth, involves the discordance or lack of agreement and consistency.[5] Although initially developed to discuss the economic and touristic usage of different types of heritage, this concept is particularly apt for discussing the legacy of the Ottoman Empire, especially Armeno-Turkish, given the dispersal and spread of its consumers across space and time.

In the multilingual and multicultural environment of the Ottoman Empire, Armeno-Turkish seemed harmonious. However, post-1915, it turned into a “dissonant heritage” for both Armenians (due to the increasing proficiency in Armenian or the language of their host country) and Turks (due to the otherization of Armenians in both political and socio-cultural contexts). The decades-long indifferent attitude towards Armeno-Turkish legacy in the scholarly and social circles of both Armenia and Turkey can also be explained by this dissonance. Only recently have valuable contributions in the field of Armeno-Turkish scholarship stimulated scholarly debates[6] on the topic.

One of the most significant questions for the researchers is to determine degree of prevalence of this phenomenon among the Ottoman Armenians as well as other inhabitants of Empire and to examine how this has changed over time. Research in recent years and emerging evidence indicate that from at least the mid-nineteenth century, there were other consumers of Armeno-Turkish among the Ottoman elite. Cankara even argues, “Turkish language written using the Armenian script especially throughout the nineteenth century might have served as a written lingua franca among the members of different ethnic, religious and linguistic groups in the Ottoman Empire”.[7] In contrast, Der Matossian suggests that Turkophone Armenians adopted Armeno-Turkish to emphasise their distinct and persistent identity from the dominant culture.[8] According Aslanian, “the reading market for Armeno-Turkish books still remains a puzzle. It seems undeniable that during the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, the bulk of the readership consisted of Catholic Armenians residing predominantly in urban centers… However, in addition to the urban markets, one cannot help but wonder how many Armeno-Turkish printed texts ended up in the countryside where no doubt literacy levels were remarkably lower than in urban centers”[9]. This divergence in scholarly opinions highlights that there is no single approach to understanding the Armeno-Turkish heritage.

To address the complex question of “who were the consumers of Armeno-Turkish?”, it is necessary to look beyond the literature, textbooks, and theatre plays that were mainly intended for the educated elite. A more comprehensive approach includes examining ego documents such as letters, diaries, and memoirs, which represent more casual, informal, and simple examples of Armeno-Turkish literary production.Referring to the topic Aslanian indicates, “alongside the voluminous output of printed works in Armeno-Turkish, there was an equally abundant but more difficult-to-access literary production in manuscript form, much of which lies scattered across archives and in manuscript collections in half a dozen countries”.[10] This idea was proven during fieldwork with the generations of repatriates from Turkey living in Armenia (2020), the most common answer about diaries/memoirs of their grandparents was “my grandma/pa used to write things in Turkish, we didn’t understand anything, we threw the copybooks out after her/his death”.[11] Luckily, some ego documents are still preserved either in private family archives or special manuscript collections and await research.[12] For instance, three handwritten memoirs in Armeno-Turkish are preserved in the collection of unpublished memoirs at the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute Foundation[13] in Yerevan.

Penon Vasilyan’s Memoir: A Case Study

This article focuses specifically on the Penon Vasilyan’s memoir written in Soviet Armenia up to 1985. The selection of this particular document is justified by two significant factors. First, written nearly a decade after the last printed book in Armeno-Turkish, Vasilyan’s memoir is considered one of the “final chords” in the tradition of Armeno-Turkish, if not the latest. This positions the memoir as a crucial piece of the historical puzzle, potentially marking the end of an era for Armeno-Turkish written works. Secondly, Eastern Armenia, known as Soviet Armenia after 1920, has traditionally not been regarded as a significant locus for the use of Armeno-Turkish. However, testimonies from interviews and preserved memoirs and letters in the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute reveal a different narrative. Armenians fleeing to Eastern Armenia from bordering regions were predominantly Armenophone, but repatriates arriving in Soviet Armenia from Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, France, and Turkey[14] brought with them the tradition of Armeno-Turkish. They used it extensively in their personal lives, highlighting a continuity of linguistic and cultural practices.

Moreover, in some instances, Armeno-Turkish functioned as a ‘secret language’ to narrate traumatic experiences, particularly because the political climate of the Soviet era was not conducive to discussions about the Ottoman past. This created an additional layer of “dissonance” as these documents, incomprehensible not only to the broader society but often even to the authors’ children and grandchildren, represented silent yet potent narratives of a displaced heritage. These ‘silent’ documents thus reveal a profound disconnection with their surrounding reality from the moment of their creation, illustrating the complex interplay between language, memory, and identity.

A Life Between Empires: Born Ottoman, Died Soviet

Penon Vasilyan’s memoir, written in the mid-1980s in Yerevan, the capital of Soviet Armenia, epitomizes the dissonant heritage discussed earlier. It is a remarkable testament of an Ottoman citizen turned Soviet resident, whose life encapsulates the dramatic shifts of the 20th century. The inscription on the first page reveals the scope of the memoir: it is “a life saga” spanning from 1909, when Vasilyan was six years old, up to 1985. The author introduces himself, noting, “Vasilian Penon was born in Dörtyol in 1903 and in 1985 wrote everything that had happened to him and everything he had eye-witnessed during his life.” [Penon Vasilyanın romanı 6 yaşdan 1909dan 1985de romanı Vasilyan Penon Dörtyolda doğmuş 1903 tarihde 1985 de bütün ömründe başına gelenleri ve gördügi geçiştigi günnerin romanını yazmışdır].

The choice of Armeno-Turkish as the language of the memoir might initially seem symbolic, emphasising cultural links with the past. However, a passage from Vasilyan’s memoir reveals more practical reasons:

I remained illiterate because I did not go to school. I did not manage to learn the Armenian language because everyone spoke Turkish in our Dörtyol. Moreover, I lived in the Turkish village until the age of 12, later we spent 3-4 years in Arabistan, then after returning at the age of 16, I became a criminal. I could not go to school. If I had not been imprisoned, I would never have learned to read and write.

[Mekdebsiz kaldığım içun yayan kaldım ermeniceyi öyrenemedim çünki bizim dörtyolda türkce dıl gonuşullar idi işte birde ben zaten türk köyinde 12 yaşa gadar türkçe idi dilim ondan sonra da arabistanda 3-4 sene galdık geri döndükten sonra da 16 yaşında hayıfcı olduk mekdebe gedemedim eyer mabusa düşmeseydim bu katarı da yazmayi öyrenemezdim mabus hanede ilazım oldu yazmak okumak][15].

Vasilyan’s limited formal education, reflected in his simple writing style filled with misspellings and grammatical errors, highlights the practical necessity of using Turkish, the lingua franca of his formative years. His choice of language indicates the complexity of his identity, shaped by the confluence of Armenian and Turkish cultures.

Dividing the story into short and long subtitles, the author initially focuses on the history and socio-economic life of Dörtyol.[16] He begins in the mid-eighteenth century when the first Armenian families were forced by the local authorities to move from Erzurum to Dörtyol. According to Vasilyan, his great-grandfather, Vasil Kehe Vasilyan, was among the first resettlers.[17]

The memoir details the genealogy of the Vasilyan family and the social, political, and cultural situation in Dörtyol, chronicling the history of a community that was once prosperous but later faced deportation, starvation, and slaughter. In the late 1800s, Dörtyol was home to 700 families. The town had three churches and three mills, as well as a large market located at the junction of four roads.[18] The main occupation of the inhabitants was the trade of oranges. Even the poorest families had at least ten orange trees, which provided an annual income of ten gold coins.[19]

Although Penon’s family also had a garden, his father Levon worked as a shoemaker in Değirmen Deresi, a Turkish village near Dörtyol.[20] The author even added a small, hand-drawn map to represent his hometown, illustrating its significance to him and providing a visual context for readers. Using a “parataxis” technique unconsciously, Penon combines day-to-day events, such as going to work, with more dramatic events, such as the death of a loved one or horrific scenes of massacres and torturous deaths. This approach allows readers to imagine the writer’s responses to the variety of his life experiences, bridging mundane and catastrophic moments seamlessly[21].

The first traumatic memories Vasilyan recounts are linked to the 1909 Adana massacres[22] and the defense of Dörtyol. The head of the village of Değirmen Deresi assisted his family when the hunt for the ‘gavurs’ (infidels) [կեվուր ավը – gevur avı in Penon’s words]began. This same village head helped Penon’s family again at the onset of the 1915 deportations. Penon’s father chose to stay with relatives, but due to deteriorating conditions, including scarcity of food and the spread of disease, Penon decided to flee. After years of displacement, in 1918, he and many other Armenian refugees managed to return to their hometown. Before 1914, the Vasilyan family consisted of 63 members, but by the time Penon returned, only a few had survived. Despite these losses, Vasilyan’s memoir highlights the complexities of Armenian and Turkish relationships. For instance, although Penon attributes the deportations to the policies of Sultan Abdulhamid II and the inaction of European countries, his narrative reveals that his interactions with individual Turks were often based on personal rather than ethnic or religious animosities. This nuanced view highlights the dissonant heritage theme, reflecting both conflict and cohabitation. Homesickness and longing for his lost homeland are recurring themes in Vasilyan’s memoir. This is poignantly illustrated by his references to Dörtyol as “vatan” or “memleket” [Turkish for “homeland”], while Soviet Armenia is simply referred to as “Mer Hayasdan” [Armenian for “Our Armenia”], with Armenian words being used sparingly. His deep attachment to Dörtyol is further emphasised by the substantial portion of the memoir—over 300 pages—dedicated to life there, compared to only brief mentions of his 35 years in Armenia.

The memoir also includes self-written poems[23] that reflect his longing and mourning for his lost homeland, particularly Cilicia. The closing poem encapsulates his enduring hope for the eventual return of Armenians to their ancestral lands, even expressing this wish as a vision he hopes to witness from the afterlife. Here are some parts of the poem:

| Now I will write about my love, | Şimdi ben yazayım benim aşkımı |

| This love makes me suffer, | bu aşk benim ağrıtyor başımı |

| It makes me cry, | akıtıyor gözlerimin yaşını |

| The echo of Cilicia in my mind | başımdaki kilikyanın sedası |

| We cannot forget about our motherland, | unutulmaz bu vatan davası |

| The melodies could change, | deişilir çalgıların havası |

| Armenians’ wounds cannot close, | eyi olmaz ermeniyin yarası |

| Until Cilicia is not our motherland | olmadıkca bize vatan kilikya |

Through these reflections, Vasilyan’s memoir provides a rich, personal account of the socio-political dynamics, cultural identity, and enduring legacy of a community deeply affected by displacement and change. It unveils the details of the “unnoticed lives” of ordinary Armenians, shedding light on their experiences, emotions, and aspirations as they navigated drastic political and social upheavals. The memoir addresses crucial questions such as “What did people feel?”, “What did they think?”, and “What did they want?” in the face of these transformations. By doing so, it offers invaluable insights into the human dimension of historical events, illustrating how ordinary lives were shaped and reshaped by the forces of history.

Conclusion

Penon Vasilyan’s memoir offers a micro-historical chronicle that illuminates the self-perception and identity of people living in a multi-religious, multi-lingual society before World War I. As a primary source, it provides invaluable insights into the social and cultural history of Ottoman Armenians and the broader cultural interactions within the Empire. The memoir illustrates the extensive use of Armeno-Turkish in daily interactions, highlighting its role in preserving Armenian heritage within the Ottoman milieu.

Vasilyan’s detailed account of life in Dörtyol and neighbouring villages enriches our understanding of the socio-economic and cultural dynamics of these communities, offering a significant resource for exploring the complexities of identity and language in a diverse imperial setting. His narrative demonstrates that Armeno-Turkish had a more common usage in everyday life than previously imagined, and even after 1915, it found a place in the geographical expanse of Soviet Armenia.

Analysing the memoir within the framework of “dissonant heritage” reveals how Vasilyan’s story disrupts and complicates straightforward historical accounts of Armenian and Ottoman interactions. His use of Armeno-Turkish indicates the persistence of cultural synthesis amid political upheaval, challenging the erasure and homogenisation of Armenian identity post-dispersal. The memoir’s creation in Soviet Armenia adds another layer of dissonance, reflecting the experiences of repatriates from diverse linguistic backgrounds. In the politically sensitive environment of Soviet times, Armeno-Turkish sometimes served as a “secret language” for recounting traumatic experiences. These “silent” documents, often incomprehensible to subsequent generations, deepen our understanding of the historical and cultural contexts from which they emerged. Thus, Vasilyan’s memoir stands as both a personal chronicle and a cultural artifact, enriching the scholarly discourse on Armeno-Turkish heritage and its enduring legacy.

[1]For the transcription of Armenian names, I use the system of the Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/armenian.pdf (Accessed 04.05.2023).

[2]Analogous examples to that of Armeno -Turkish are encountered among other ethnic groups in the Ottoman Empire, namely Greco-Turkish (Karamanlidika), Judeo-Turkish or Hebrew-Turkish, Cyrillic Turkish, Syro -Turkish. However, as J. Strauss mentions “since bilingualism was a common feature among Armenians, they were always much more familiar with the Turkish language than Greeks were, and Turkish books in Armenian script (far more numerous than those in Karamanli) found a wide readership”, Strauss, J., “The Millets and the Ottoman Language. The Contribution of Ottoman Greeks to Ottoman Letters (19th – 20th Centuries)”, Die Welt Des Islams 35, no. 2 (1995), pp. 189-249, p. 211 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1571230 (Accessed 04.05.2023). For detailed information see also Between Religion and Language. Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, ed. by E. Balta and M. Ölmez (Istanbul, 2011) pp. 15-318; Balta, E., “Translating Books from Greek into Turkish for the Karamanli Orthodox Christians of Anatolia (1718-1856)”, International Journal Turkish Studies, 23 (1&2) (2017) pp. 19-33, https://evangeliabalta.com/old/kitap/61_review.pdf . (Accessed 15.05.2023)

[3] For detailed information see Stepanyan H., List of Armenian manuscripts, Armenian-Turkish materials and Armenian-Turkish manuscripts, Yerevan Mashtots Library and Manuscripts of the Holy Etchmiadzin Mother See , Part A (Yerevan, 2008, in Armenian).

[4] [Till 1990s] The word heritage had a simple and generally accepted primary meaning, it was the collective generalisation derived from the idea of an individual’s inheritance from a deceased ancestor. [In the mid 1990s] The word has acquired much wider commonly understood meanings and is applied in a wide variety of contexts. It is used as a synonym for any relict, physical survival from the past. – For more detailed information see Tunbridge J. E., Ashworth G.J, Dissonant Heritage. The Management of the Past as a Resource in the Conflict (England, 1996), p. 2.

[5] Tunbridge J. E., Ashworth G.J, Dissonant Heritage, p. 20

[6] See for instance Pamukciyan, K., Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Edebiyat, ed. Osman Köker (İstanbul, 2002); Mignon, L., A pilgrim’s progress: Armenian and Kurdish literatures in Turkish and the rewriting of literary history, Patterns of Prejudice, 48:2, 2014, pp. 182-200; Ergen S., Son dönem Osmanlı Yemek Kültüründe Ermeni Mutfağının Katkısı Ermeni harfli Türkçe yemek kitapları (İstanbul, 2019). Çelik H., Sargsyan, A, “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies”, Diyâr. Zeitschrift für Osmanistik, Türkei- und Nahostforschung, 3. Jg. 2 (2022), pp. 161-189; Uygur, K., Yalkin, C., Uygur, S., “Market-making strategies in Tanzimat era Istanbul: The quest for an elusive cosmopolitanism”, Business History (2023), pp. 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2023.2279128. Uygur, K., “Intercommunal Encounters Between Ottoman Turkish and Armenian Literati: The Case of Armeno-Turkish Print Media”, Turkish Area Studies Review (TAS Review) (2022), pp. 32-38, Masayuki U., “One Script, Two Languages: Garabed Panosian and His Armeno-Turkish Newspapers in the Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Empire”, Middle Eastern Studies 52. 4 (2016), pp. 605– 622, Kiraz, E., Osmanlı Mizah Basınının Başlangıcı: Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Mizah Gazetesi Zvarcakhos “Latifeci” (1856) (İstanbul, 2024).

[7] Cankara, M., “Rethinking Ottoman Cross-Cultural Encounters: Turks and the Armenian Alphabet”, Middle Eastern Studies 51:1 (2015), pp. 1-16, p. 1.

[8] Der Matossian B., “The Development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T‘rk‘erēn) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire Marking and Crossing Ethnoreligious Boundaries”, Intellectual History of the Islamicate World, 8 (2020) pp. 67–100, p. 71.

[9] Aslanian, S. D., ““Prepared in the Language of the Hagarites”: Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian’, Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, vol. 25 (2016), pp. 54–86, p. 71.

[10] Ibid, p. 61

[11] For more detailed information see Melkonyan R., Poghosyan N. “Escape from the Motherland: Repatriation from Turkey to Armenia (1920-1980s) (Yerevan, 2022) (in Armenian).

[12]Survivors of the Armenian Genocide started to write their stories from the time when the Genocide itself was still going on. These Armenians pursued opportunities to tell their stories of survival and the destruction of their communities, mainly in the Armenian language but also in English and other languages. While a few of these memoirs achieved a measure of fame, more of them are obscure; but, of course, fame is not a measure of their value. Each book has value as a historical document and as a carrier of memory. For more detailed information and the list of published memoirs see Genocide Survivor Memoirs in Armenian & English, 1918-1955, https://naasr.org/blogs/treasures-of-naasrs-mardigian-library/genocide-survivor-memoirs-in-armenian-english-1918-1955 (Accessed 04.05.2023).

[13] There are nearly 500 unpublished memoirs in the collection of «Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute» Foundation,For detailed information see The AGMI Collection of Unpublished Memoirs, http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/18_ag_20.php( Accessed 25.05.2023).

[14] For detailed information about the Repatriation of Armenians in 1946-1948 see Pattie, S., “From Centers to Periphery: ‘Repatriation’ to the Armenian Homeland in the Twentieth Century,” in Homecomings: Unsettling Paths of Return, eds. Fran Markowitz and Anders H. Stefansson, (Oxford: Lexington Books, 2004), pp. 109-124.

[15] For the transcription of Armeno-Turkish I use the system developed by Çelik and Sargsyan, “Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish”.

[16] Detailed information on the Armenian Community of Dörtyol before 1915 in English is available on https://www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-adana/doertyol.html

[17] The memoirs by P. Vasilian N 338 (206), p. 4.

[18] The memoirs by P. Vasilian N 338 (206), p. 23.

[19] The memoirs by P. Vasilian N 338 (206), p. 10.

[20] The memoirs by P. Vasilian N 338 (206), p. 2.

[21] For detailed information on “parataxis” see North P., Diaries and Silence, in Archival Silences: Missing, Lost and, Uncreated Archives (1st ed.), ed. by Moss, M., & Thomas, D. (Routledge,2021) p. 210.

[22] For detailed information see Der Matossian, B., Horrors of Adana: Revolution and Violence in the Early Twentieth Century (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022).

[23] It is worth to mention that there is a large tradition of writing Armeno-Turkish folkloric songs. The ethnographer Dr. Prof. Verjiné Svazlian has, for a number of years, investigated the memoirs and the Turkish-language folk songs depicting the events of the Genocide on the basis of the abundant materials․ She herself has written down from the aged male and female representatives of Western Armenians, who had witnessed and suffered the Genocide; moreover, she has skillfully put together their factual data with exact historical testimonies and has revealed the historical authenticity of the vivid and emotional images of the reality reflected in the oral tradition. See Svazlianö V., “The Armenian Genocide In The Memoirs And Turkish-Language Songs Of The Eye-Witness Survivors”, https://hyetert.org/1999/01/01/the-armenian-genocide-in-the-memoirs-and-turkish-language-songs-of-the-eye-witness-survivors/ (accessed 25.05.2023).