Milletimizin faziletlerini medh, ve kusurlarını ise, ah u oflar çekerek, beyan iylememiz azkasirutyuna muvafıkdır zann ideriz:”[1] Garabed Panosian, 1860

[1] “We supposed that praising our nation’s virtues and desperately speaking of its imperfections fits for national love.” Garabed Panosian, “Meyli Tabii,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), April 15, 1860. Translation Arif Tapan.

Arif Tapan (Social Sciences University of Ankara)

I. Introduction: The Birth of Münâdî-i Erciyes in Ottoman Print Culture

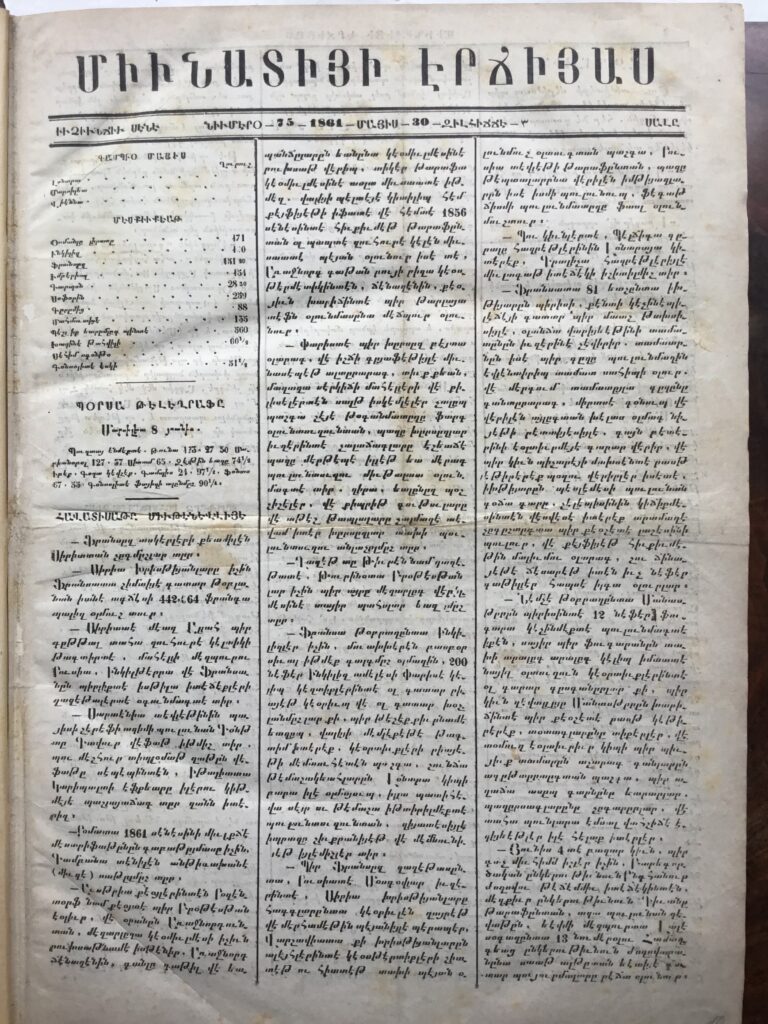

Münâdî-i Erciyes (1859-1862), a notable periodical from the mid-19th century Ottoman Empire, was first introduced to the Ottoman press on June 1, 1859. It was initiated by Garabed Panosian, an Ottoman Armenian from Kayseri (Caesarea), who was born between 1826 and 1828 and lived until 1905. The periodical was published every fortnight in Istanbul and written in Armeno-Turkish, using the Armenian script to write Turkish.[1] Initially titled Münadiyi Erciyas-Risaleyi Devriye İlmiye Sanatiye Adabiye ve Sayire (Herald of Argeus – A Pamphlet About Science, Arts, Decency, etc.), the publication typically comprised eight pages per issue during 1859 and 1860. From 1861 onwards, the publication transitioned into a newspaper format, reflecting both an increase in content diversity, periodicity and a wider distribution range.[2] This evolution highlights the growing influence and adaptation of Münâdî-i Erciyes to meet the intellectual demands of the Ottoman public. The transformation from a ‘risale’ (pamphlet) to a newspaper indicates a significant shift towards more regular and varied content, aligning with the broader trends in the Ottoman press of the time.

Building on this historical context, in this introductory article, I will first emphasise the significance of the Münâdî-i Erciyes newspaper and elucidate its editorial vision. Following this, I will examine two primary themes that emerged from an analysis of Münâdî-i Erciyes: the cultivation of millet and the education of women and young girls. Münâdî-i Erciyes remains largely unexplored in existing literature due to the limited research on the Armeno-Turkish press. Notably, Ueno was one of the first scholars to reference the name Münâdî-i Erciyes in his work,[3] which primarily focused on the journalism career of Garabed Panosian through his various publications. On the other hand, Cankara, in addition to his works on Armeno-Turkish literature, focused on the diversity of the Armeno-Turkish press and mentioned Münâdî-i Erciyes in one of his introductory articles on print media.[4] Uygur, in her PhD dissertation, and subsequent articles examined mainstream print media representing different Armenian denominations, but her works focused on Panosian’s more mainstream media, Manzume-i Efkâr and Varaka-i Havadis rather than Münâdî-i Erciyes.[5]

To understand Ottoman Armenian journalism, it is crucial to examine Panosian’s very first newspaper. Ottoman Armenians were pioneers in journalism within the Empire, with the number of Armenian and Armeno-Turkish newspapers surpassing their Turkish counterparts.[6] Unlike many other journalists or authors of his time, Panosian was not from the upper class. He was a mid-land Anatolian entrepreneur, a dedicated soul aiming to cultivate his own millet and the wider populace. His newspapers were among the first to form public opinion and resist some authorities, such as the Patriarchate, to inform and enlighten the people.

Given this backdrop, previous studies that have significantly contributed to the literature on the Armenian and Armeno-Turkish press have not extensively examined Münâdî-i Erciyes, an early Ottoman/Turkish culture, science and arts periodical. This oversight presents an opportunity to explore this influential publication, offering new insights into the broader social and cultural aspirations of Ottoman Armenians and the intellectual climate of the 19th-century Ottoman world.

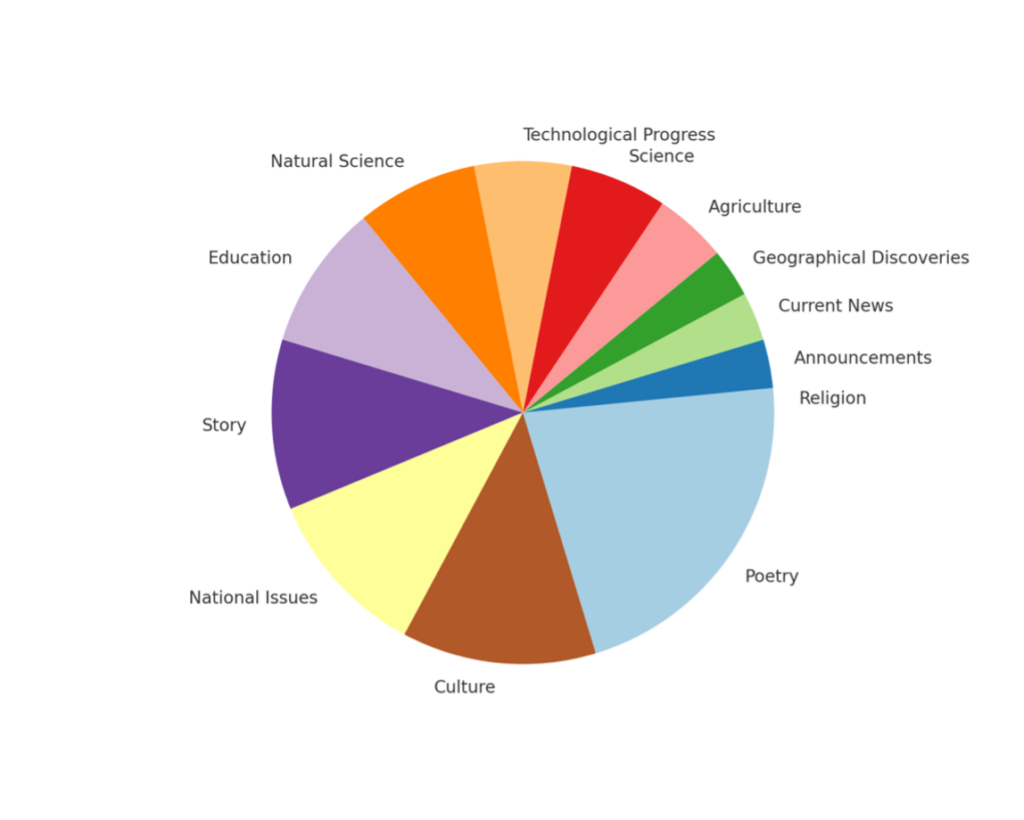

II. The Editorial Vision of Münâdî-i Erciyes: Shaping the Ottoman Reader

Münâdî-i Erciyes was presented to the Ottoman reading public in 1859 with a diverse range of content, covering many different genres. This diversity and richness of content suggests that the newspaper aimed to engage an Ottoman readership sensitive to the intellectual, cultural, and social issues of the Empire. The editorial policy was clearly designed to reflect this aim. Below, a table would illustrate the variety of content that Münâdî-i Erciyes offered in its 1859 issues and the space each type of content occupied.

Table I. The distribution of Münâdî-i Erciyes’s content diversity in 1859

In the ‘Mukaddeme’ (Preface), the opening article of Münâdî-i Erciyes’s first issue, Garabed Panosian announced his purpose in publishing the periodical and the range of its content. Panosian articulated that the main purpose of Münâdî-i Erciyes was, firstly, to enlighten his compatriots, secondly, to enlighten people who understood Turkish better than Armenian, and thirdly, to express his views. He further promised future detailed explanations on the necessity of both the Turkish and Armenian languages.

The main purposes of Münâdî-i Erciyes were to enlighten his compatriots, to educate those who understood Turkish better than Armenian, and to express his views. Future issues would elaborate on the necessity of learning both the Turkish and Armenian languages.[7]

Half of the risale[8] (pamphlet) would cover topics such as zoology, phytology, mineralogy, silk, sugar, farming, geography, world history, didactic stories, and updates on world governments, along with a poem in each issue. The other half would continue the translation of Télémaque.[9]

Panosian’s primary motivation for publishing the pamphlet was to educate the Ottoman reading public and ‘enlighten’ them on various subjects. The term ‘to enlighten’ derived from the Arabic word ‘tenvir [etmek]’, indicates his aim to introduce readers to positive sciences, culture, arts, and moral ethics. His inclusion of a translation of the French Télémaque further demonstrates his effort to familiarise the Ottoman public with European literature.

III. Cultivating the Millet: Intellectual and Moral Development in Münâdî-i Erciyes

The theme of community (millet) cultivation is central to Münâdî-i Erciyes. Panosian frequently lamented the state of his nation, emphasising the importance of intellectual and moral development. He believed that the nation’s progress depended on its commitment to education and enlightenment.

In an editorial from 1859, Panosian criticises the neglect of useful publications and the societal preference for frivolous activities over intellectual pursuits. He emphasises the millet’s need to awaken from ignorance and strive towards education and enlightenment:

A great person has died, and we mourn and cry, but what if a book, a newspaper, or another useful publication dies, closes down, its author gives up, or truly passes away? How much should we mourn and cry? As much as for a noble person? No, a thousand times more… Then let our nation cry, for since the year 1861, approximately twenty-eight publications, that is, newspapers and pamphlets, have disappeared. What is the reason for this? Have all their authors died, or have they become rich and abandoned their efforts, or did they write something against the state and were shut down? No, no, no! Our nation has fallen asleep, reading and writing have been sacrificed to ignorance, taverns, lounges, cafes, casinos, and so on have taken the place of libraries.[10]

The quote reflects Panosian’s deep concern for the intellectual stagnation of his society and his call for a revival of intellectual and educational values to foster communal progress. Panosian often calls for a collective effort to embrace education and reform, highlighting the disparity between the rich natural resources of the millet and its socio-economic inaction due to ignorance and laziness. In an editorial from 1859, he contrasts the community’s past glories with its current state of ignorance and passivity, emphasising his dedication to enlightening his people:

Every millet, big or small, takes pride in its achievements according to its abilities and merits. Our millet too had commendable deeds in the past, as history testifies, but for centuries, and especially now, there is no action or achievement to take pride in. Instead, we, like delusional poor people boasting of their deceased father’s wealth and achievements, are content with reading our ancient histories and remain submerged in a sea of ignorance. Yes, many of our wealthy and influential people strive to destroy rather than build, and to close rather than open…miserable and unfortunate millet. If someone from other millets, curious about our current state, asked about our morals, arts, education, knowledge, and our enthusiasm for reading and writing, what answer could we give… nothing, nothing, nothing![11]

He further points out that wealth follows wisdom and effort, pointing out that the nation’s current state is due to its own negligence and idleness. Panosian believes that the millet’s socio-economic stagnation is self-inflicted, stemming from a lack of intellectual and practical engagement. He suggests that the potential for wealth and progress exists but requires a dedicated commitment to education and industriousness, reinforcing his call for community reform and enlightenment.[12]

IV. Educating Women and Girls: Foundation for a Cultivated Society

Panosian’s efforts extended beyond mere publication. He was a community leader and an advocate for education, particularly for women and young girls. His establishment of a girls’ school shows his dedication to improving literacy and educational standards within his community. The editorials of Münâdî-i Erciyes reveal Panosian’s deep concern for the intellectual and moral development of Ottoman society, highlighting issues such as the lack of interest in reading and writing, the importance of education for advancement, and the critical role of women in societal progress.

In his 1859 and 1860 issues, Panosian envisioned Ottoman women as the most constitutive figures of society, emphasising the need for their education and cultivation. He was particularly insistent and determined about the education of girls. For Panosian, the advancement of a millet depended on its commitment to decency, good manners, wealth, and happiness, which he believed were inherently linked to literacy and education. He contrasts enlightened nations with those left in the darkness of illiteracy, highlighting the transformative power of education.

In one of his articles, Panosian articulates the importance of girls’ education as follow:

Our intention here is to emphasise the importance of girls’ education and teaching children a clean language. Seeking the opinion and efforts of the elders on this matter is like setting sail in calm weather. Girls are necessary for young men, and young men are also necessary for girls. Both girls and young men are necessary for the entire country. Therefore, we must prioritise girls’ education, strive tirelessly, and make sacrifices for this cause.[13]

Panosian portrays a society divided into two parts: one that has adapted to the current conditions of the age through knowledge and education, and another that suffers due to total ignorance. For him, education is the only constitutive element of social advancement. He envisions a well-mannered and educated society, with a particular focus on women and young girls as the primary beneficiaries of educational reforms.

In his series of articles titled ‘Girls’ School’ (Kızlar Mektebi), serialised for a long time in Münâdî-i Erciyes, he explicitly underlines the priority of women’s and girls’ education:

To love a child fully and truly is only possible by transforming the child from an animal to a human being, and this is only possible by nourishing the child’s soul, that is, by filling their minds with knowledge, by teaching them to read, to write, to learn, to know, and by striving wholeheartedly to make them know what the wisest of men knows.[14]

Panosian emphasises that parents who love their children should prioritise their education, advocating for the establishment of schools for girls before boys:

Because the easiest and the best way for a nation to make the science and knowledge it possesses permanent and useful and to spread it is to create well-behaved, knowledgeable, and skilful girls and women. Because, as we have said before, what men learn only benefits themselves, whereas what women learn will undoubtedly be passed on to their children and bequeathed to them.[15]

Throughout the ‘Girls’ School’ articles, Panosian frequently indicates the importance of women’s education. He argues that only women and mothers can transmit knowledge to new generations, disseminate it, and make it permanent. Educated women are essential for raising educated children, creating a cycle of continuous improvement and enlightenment within society.

For example, in an editorial from 1860, Panosian stresses the necessity of girls’ education for millet progress and states:

Although our nation is currently in a disgraceful state, we cannot deny that many nations have emerged from barbarism into enlightenment through the light of knowledge and science, casting their radiance upon the world, while we remain abandoned in the sleep of ignorance and poverty. This condition is not worthy of a renowned nation with a four-thousand-year history.[16]

Panosian’s editorial highlights the stark contrast between the potential for progress and the current state of inertia. By advocating for the education of girls, he emphasises that uplifting the country’s women is crucial to breaking the cycle of ignorance and poverty. This call for educational reform reflects a broader vision for societal transformation, where the empowerment of women becomes the foundation for a more enlightened and prosperous community.

V. Reflecting on Münâdî-i Erciyes: Historical Significance and Contemporary Insights

The significance of Münâdî-i Erciyes lies not only in its content but also in the broader context of the 19th-century Ottoman Empire’s cultural and intellectual landscape. Understanding this periodical requires situating it within the larger framework of science-culture publishing that emerged during this time, including journals, magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets. The publication of Münâdî-i Erciyes reflects a period of growing interest in the positive sciences and cultural enrichment among the Ottoman public. Authors, publishers, printing press owners, and administrators recognised the need to disseminate knowledge and foster enlightenment, particularly after the mid-19th century. Panosian’s initiative to publish a newspaper focusing on science, culture, and literature in 1859, with a strong emphasis on the cultivation of the millet and the education of women and young girls, exemplifies this trend.

Panosian’s motivations for publishing Münâdî-i Erciyes were rooted in a broader movement towards modernisation and enlightenment within the Ottoman Empire. His dedication to education, especially for women, and his advocacy for the cultivation of intellectual and moral values were aligned with the global currents of the time. While the Ottoman Empire did not achieve scientific progress simultaneously with Europe, its unique modernisation processes were influenced by a combination of internal dynamics and external pressures. The editorials from Münâdî-i Erciyes reveal Panosian’s deep concern for the intellectual and moral development of Ottoman society. His call for a collective effort to embrace education and reform, his emphasis on the importance of literacy and enlightenment, and his vision of an educated and morally sound society indicates the periodical’s enduring relevance. Panosian’s work serves as a testament to the complex interplay between local and global influences in the 19th century Ottoman Empire.

In conclusion, Panosian’s Münâdî-i Erciyes was more than a periodical; it was a manifestation of his vision for an enlightened and educated Ottoman society. His contributions to identity, education, and social progress are crucial for understanding the broader cultural dynamics of the time. By placing Münâdî-i Erciyes within the context of 19th century Ottoman modernisation and global enlightenment, we gain valuable insights into the period’s intellectual currents and Panosian’s enduring legacy.

REFERENCES:

“Memurini Münadiyi Erciyas.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), June 15, 1861.

Aslanian, Sebouh D. “Prepared in the Language of the Hagarites: Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian.” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, vol. 25 (2016): 54-86.

Cankara, Murat. “Mecmua-i Havadis’ten Agos’a: Ermenice Bilmeyen Ermeniler ve Basın.” Toplumsal Tarih 301 (Jan. 2019): 8-11.

Cankara, Murat. “Armeno-Turkish Writing and the Question of Hybridity.” in An Armenian Mediterranean, edited by Kathryn Babayan and Michael Pifer, 173-191. Michigan: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Cankara, Murat. “Başka Bir Türkçe Mümkün Müydü?” Toplumsal Tarih 312 (Dec. 2019): 4-7. Cankara, Murat. “Çifte Maduniyet, Çifte İşlev: Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Basında Dil ve Kimlik.” Ankara Üniversitesi İLEF Dergisi 2, no. 2 (Nov. 2015): 105-30.

Der Matossian, Bedross. “The Development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T’rk’erēn) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire: Marking and Crossing Ethnoreligious Boundaries.” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 8, 1 (2020): 67-100.

Panosian, Garabed. “Gağant 1860.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Jan. 1, 1860.

Panosian, Garabed. “Kızlar Mektebi.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Nov. 1, 1859.

Panosian, Garabed. “Meyli Tabii.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), April 15, 1860.

Panosian, Garabed. “Milletce (Azkayin).” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Aug. 15, 1859.

Panosian, Garabed. “Mukaddeme.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), June 15, 1859.

Panosian, Garabed. “Tonel.” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Sept. 15, 1859.

Ueno, Masayuki. “One script, two languages: Garabed Panosian and his Armeno-Turkish newspapers in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire.” Middle Eastern Studies 52/4 (2016): 605-622.

Uygur, Kübra, and Yıldız Deveci Bozkuş. “1863 Ermeni Milleti Nizamnamesi’nin Yansımalarını Varaka-i Havadis Üzerinden Okumak.” Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 13 (1), (2022): 94-104.

Uygur, Kubra, Cagri Yalkin, and Selcuk Uygur. “Market-Making Strategies in Tanzimat Era Istanbul: The Quest for an Elusive Cosmopolitanism.” Business History (Nov. 2023): 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2023.2279128

Uygur, Kübra. “Intercommunal Encounters Between Ottoman Turkish and Armenian Literati: The Case of Armeno-Turkish Print Media.” Turkish Area Studies Review 39, (Spring 2022): 32-38.

Uygur, Kübra. “Understanding a Hybrid Print Media and Its Influence on Public Opinion: The Case of Armeno-Turkish Periodical Press in the Ottoman Empire, 1850-1875.” PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 2021.

[1] The term refers to Ottoman-Turkish texts written in the Armenian scripts. For more detailed information on Armeno-Turkish as a phenomenon, please see: Sebouh D. Aslanian, “Prepared in the Language of the Hagarites: Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, vol. 25 (2016): 54-86; Murat Cankara, “Armeno-Turkish Writing and the Question of Hybridity,” in An Armenian Mediterranean, ed. Kathryn Babayan and Michael Pifer (Michigan: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 173-191; Bedross Der Matossian, “The Development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T’rk’erēn) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire: Marking and Crossing Ethnoreligious Boundaries,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 8, 1 (2020): 67-100.

[2] Münâdî-i Erciyes was also distributed in İzmir, Edirne, Kayseri, Bursa, Tokat, Adana, Tarsus, Maraş, Sivas, Merzifon, Trabzon, and even in Manchester and Egypt. See “Memurini Münadiyi Erciyas,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), June 15, 1861.

[3] Masayuki Ueno, “One script, two languages: Garabed Panosian and his Armeno-Turkish newspapers in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire,” Middle Eastern Studies 52/4 (2016): 605-622.

[4] Murat Cankara, “Başka Bir Türkçe Mümkün Müydü?” Toplumsal Tarih 312 (Dec. 2019): 4-7. Also see Murat Cankara, “Çifte Maduniyet, Çifte İşlev: Ermeni Harfli Türkçe Basında Dil ve Kimlik,” Ankara Üniversitesi İLEF Dergisi 2, no. 2 (Nov. 2015): 105-30; Murat Cankara, “Mecmua-i Havadis’ten Agos’a: Ermenice Bilmeyen Ermeniler ve Basın,” Toplumsal Tarih 301 (Jan. 2019): 8-11.

[5] Kübra Uygur, “Understanding a Hybrid Print Media and Its Influence on Public Opinion: The Case of Armeno-Turkish Periodical Press in the Ottoman Empire, 1850-1875” (PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 2021). Also see Kübra Uygur, “Intercommunal Encounters Between Ottoman Turkish and Armenian Literati: The Case of Armeno-Turkish Print Media,” Turkish Area Studies Review 39, (Spring 2022): 32-38; Kübra Uygur, and Yıldız Deveci Bozkuş, “1863 Ermeni Milleti Nizamnamesi’nin Yansımalarını Varaka-i Havadis Üzerinden Okumak,” Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 13 (1), (2022): 94-104.

[6] Kubra Uygur, Cagri Yalkin, and Selcuk Uygur, “Market-Making Strategies in Tanzimat Era Istanbul: The Quest for an Elusive Cosmopolitanism,” Business History (Nov. 2023): 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2023.2279128

[7] “Münadiyi Erciyasın evvela maksedi, başlıca kendi hemşehrilerinin, saniya, Ermeniceden pek çok ziyade, lisanı Türkiyi anlaya bilen zevatın tenviri içün, ve salisa . . . kelamlerini, irad iyledikden sonra, ilerude khasseten gerek lisanı Türkinin elzemiyeti, ve gerek lisanı Ermeniyanın vacibiyyeti hakkında, tafsilen bahs u beyan idecegimiz ikhbar olunur:” Garabed Panosian, “Mukaddeme,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), June 15, 1859.

[8] Münâdî-i Erciyes was initially called as risale (pamphlet) and later evolved into a newspaper in the modern sense. To avoid confusion in this article, it will be referred to as a newspaper, except when directly quoting from the publication, where it will be referred to as a risale.

[9] “Risaleyi mezburemizde, bu lisan üzre, nısfı hayvanata, nebatata ve madeniyate dayir ulum u sanatlerden, ve khususiyle ipekden, şekerden ve çiftcilikden. coğrafiaden, tarikhlerden ve adabi hikâyelerden bahs olundukdan başka, dünyade bulunan payitakhtlerin dakhi ahvalı hazırelerin ifade, ve her defade birer adet şir dakhi derc. ve diger nısfında ise, yalınız kazayayi Delemakın tercümesine devam olunacakdır:” Garabed Panosian, “Mukaddeme,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), June 15, 1859.

[10] Garabed Panosian, “Milletce (Azkayin),” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Aug. 15, 1859.

[11] Garabed Panosian, “Tonel,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Sept. 15, 1859.

[12] Garabed Panosian, “Tonel,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Sept. 15, 1859.

[13] “Buracıkda niyetimiz kızların okumuş olması, ve çocuklarına temiz lisan öyrenmesini bahs iylemekden ibaret olduğundan, kızlar için mekteb lazım dır deyu, ikhtiyarlere müracaat itmek, ve keyfiyeti anlerin reyine ve ğayretine teslim itmek, sakin havada yelken açmaya benzer, kızlar delikanlılara lazım dır, ve deli kanlılar dakhi kızlara lazım olub, gerek kızlar ve gerek delikanlılar ise, bütün millete lazım dır, dimek dir ki, bizler kendumizi kayırıb, başımızın çaresin bir yıl, bir ay, bir hefte, bir gün, bir saat, ve bir dakıka evvel, can ile, ten ile, her şeyden ve her elzemiyetden evvel, kızların okumasına, dilimizi temiz öyrenmesine, çalışıb, yorulub, ğayret, himmet, ve fedakârlık iylemeliyiz” Garabed Panosian, “Kızlar Mektebi,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Nov. 1, 1859.

[14] Garabed Panosian, “Kızlar Mektebi,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Nov. 15, 1859.

[15] Garabed Panosian, “Kızlar Mektebi,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Nov. 15, 1859.

[16] Garabed Panosian, “Gağant 1860,” Münadiyi Erciyas (Istanbul), Jan. 1, 1860.